Clothing in the ancient world

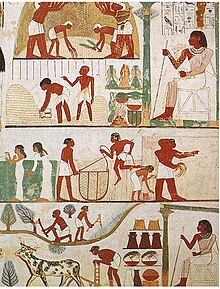

Other animal-based products such as pelts were reserved for priests and eventually were adopted by only the highest class of ancient Egyptian citizenry.

[2] Linen is light, strong and flexible which made it ideal for life in the warm climate,[3] where abrasion and heat would wear and tear at clothing.

[5] A complete lack of clothing, however, was often associated with youth or poverty; it was common for children of all social classes to be unclothed up to the age of six, and for slaves to remain unclad for the majority of their lives.

Although there was no prominent difference between the cosmetics styles of the upper and lower class, noble women were known to pale their skin using creams and powders.

Although heads were shaven as both as a sign of nobility[10] and due to the hot climate, hairstyle was a huge part of ancient Egyptian fashion through the use of wigs.

[11] In the court, the more elegant examples had small goblets at the top filled with perfume; Pharaohs even wore wig beards for certain special occasions.

[11] There is evidence of cheaper wigs made from wool and palm fibres, which were further substituted the woven gold used in its more expensive counterpart with beads and linen.

the nemes headdress, made from stiff linen and draped over the shoulders was reserved for the elite class to protect the wearer from the sun.

A peculiar ornament which the Egyptians created was gorgerin[dubious – discuss], an assembly of metal discs which rested on the chest skin or a short-sleeved shirt, and tied at the back.

[13] Accessories were often embellished with inlaid precious and semi-precious stones such as emeralds, pearls, and lapis lazuli, to create intricate patterns inspired from nature.

Copper was used in place of gold, and glazed glass or faience – a mix of ground quartz and colorant – to imitate precious stones.

[21] The earliest and most basic garment was the ezor (/eɪˈzɔːr/ ay-ZOR)[22] or ḥagor (/xəˈɡɔːr/ khə-GOR),[23] an apron around the hips or loins,[24] that in primitive times was made from the skins of animals.

[24] The kuttoneth corresponds to the undergarment of the modern Middle Eastern agricultural laborers: a rough cotton tunic with loose sleeves and open at the breast.

[24] It consisted of a large rectangular piece of rough, heavy woolen material, crudely sewn together so that the front was unstitched and with two openings left for the arms.

From this simple item of the common people developed the richly ornamented mantle of the well-off, which reached from the neck to the knees and had short sleeves.

[24] This, like the me'il of the high priest, may have reached only to the knees, but it is commonly supposed to have been a long-sleeved garment made of a light fabric, probably imported from Syria.

[25] The Torah commands that Israelites wear tassels or fringes (ẓiẓit, /tsiːˈtsiːt/ tsee-TSEET[29] or gedilim, /ɡɛˈdiːl/ ghed-EEL[30]) attached to the corners of garments (see Deuteronomy 22:12, Numbers 15:38).

[24] Hebrew peasants undoubtedly also wore head coverings similar to the modern keffiyeh, a large square piece of woolen cloth folded diagonally in half into a triangle.

[24] The fold is worn across the forehead, with the keffiyeh loosely draped around the back and shoulders, often held in place by a cord circlet.

[34][33] Shawls, dictated by Jewish piety, and other forms of head coverings were also worn by ancient Israelite women in towns such as Jerusalem.

Women dressed similarly in most areas of ancient Greece although in some regions, they also wore a loose veil as well at public events and market.

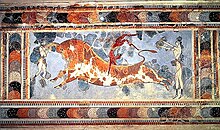

Myths relate that after this prohibition, a woman was discovered to have won the competition while wearing the clothing of a man—instituting the policy of nudity among the competitors that prevented such embarrassment again.

At its maximum extent during the foundation period of Rome and the Roman kingdom, it flourished in three confederacies of cities: of Etruria, of the Po valley with the eastern Alps, and of Latium and Campania.

Probably the most significant item in the ancient Roman wardrobe was the toga, a one-piece woolen garment that draped loosely around the shoulders and down the body.

A woman convicted of adultery might be forced to wear a toga as a badge of shame and curiously, as a symbol of the loss of her female identity.

Later, during the French Revolution, an effort was made to dress officials in uniforms based on the Roman toga, to symbolize the importance of citizenship to a republic.

These little depictions show that usually men wore a long cloth wrapped over their waist and fastened it at the back (just like a close clinging dhoti).

The normal attire of the women at that time was a skirt up to knee length leaving the waist bare, and cotton head dresses.

The most common attire of the people at that time was a lower garment called antariya, generally made of cotton, linen or muslin and decorated with gems, and fastened in a looped knot at the centre of the waist.

Typically kings, priests, and high officials would wear kaunakes down to the floor and these skirts would be embedded with ornaments and tassels and fringes.