Coactivator (genetics)

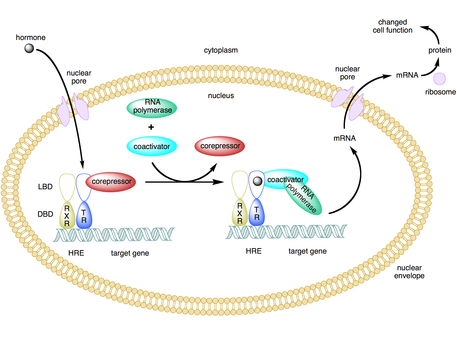

[3][4][5] The use of activators and coactivators allows for highly specific expression of certain genes depending on cell type and developmental stage.

[4][7][11] In this method, an activator binds to an enhancer site and recruits a HAT complex that then acetylates nucleosomal promoter-bound histones by neutralizing the positively charged lysine residues.

[4][11] Acetylation by HAT complexes may also help keep chromatin open throughout the process of elongation, increasing the speed of transcription.

[12] Acetylation is crucial for synthesis, stability, function, regulation and localization of proteins and RNA transcripts.

[4][7][11] This causes the chromatin to close back up from their relaxed state, making it difficult for the transcription machinery to bind to the promoter, thus repressing gene expression.

[1][7][16] This enables each cell to be able to quickly respond to environmental or physiological changes and helps to mitigate any damage that may occur if it were otherwise unregulated.

[14][21] The coactivators that regulate them can be easily replaced with a synthetic ligand that allows for control over an increase or decrease in gene expression.