Activator (genetics)

[1] Activator DNA-binding domains come in a variety of conformations, including the helix-turn-helix, zinc finger, and leucine zipper among others.

[2] Activators also have unique sequences of amino acids with side chains that are able to interact with the functional groups in DNA.

[2][3] Thus, the pattern of amino acid side chains making up an activator protein will be complementary to the surface features of the specific DNA regulatory sequence it was designed to bind to.

[1][2][3][4] This is done through various mechanisms, such as recruiting transcription machinery to the promoter and triggering RNA polymerase to continue into elongation.

[1][2][3][4] Activator-controlled genes require the binding of activators to regulatory sites in order to recruit the necessary transcription machinery to the promoter region.

[2] In prokaryotes, activators tend to make contact with the RNA polymerase directly in order to help bind it to the promoter.

[2] In prokaryotes, genes controlled by activators have promoters that are unable to strongly bind to RNA polymerase by themselves.

Activators may bend the DNA in order to better expose the promoter so the RNA polymerase can bind more effectively.

[2][3][4] In eukaryotes, activators have a variety of different target molecules that they can recruit in order to promote gene transcription.

[1][2] These coactivator molecules can then perform functions necessary for beginning transcription in place of the activators themselves, such as chromatin modifications.

[1][2] DNA is much more condensed in eukaryotes; thus, activators tend to recruit proteins that are able to restructure the chromatin so the promoter is more easily accessible by the transcription machinery.

[1][2] Some proteins will rearrange the layout of nucleosomes along the DNA in order to expose the promoter site (ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes).

[2][3] In eukaryotes, usually more than one activator assembles at the binding-site, forming a complex that acts to promote transcription.

[3] In its inactive form, the activator is unable to bind to DNA and promote transcription of the maltose genes.

[3][4] This conformational change "turns on" the activator by allowing it to bind to its specific regulatory DNA sequence.

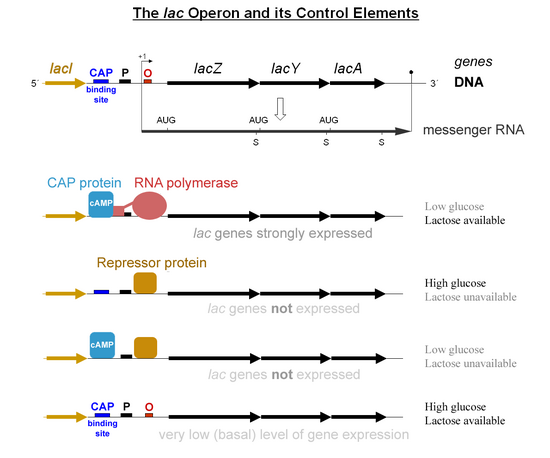

[5] Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is produced during glucose starvation; this molecule acts as an allosteric effector that binds to CAP and causes a conformational change that allows CAP to bind to a DNA site located adjacent to the lac promoter.