Czech language

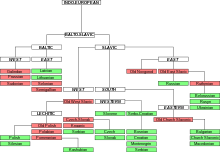

Czech is closely related to Slovak, to the point of high mutual intelligibility, as well as to Polish to a lesser degree.

[8] Czech has a moderately-sized phoneme inventory, comprising ten monophthongs, three diphthongs and 25 consonants (divided into "hard", "neutral" and "soft" categories).

Czech is distinguished from other West Slavic languages by a more-restricted distinction between "hard" and "soft" consonants (see Phonology below).

Around the 7th century, the Slavic expansion reached Central Europe, settling on the eastern fringes of the Frankish Empire.

The diversification of the Czech-Slovak group within West Slavic began around that time, marked among other things by its use of the voiced velar fricative consonant (/ɣ/)[10] and consistent stress on the first syllable.

[22] During the national revival, in 1809 linguist and historian Josef Dobrovský released a German-language grammar of Old Czech entitled Ausführliches Lehrgebäude der böhmischen Sprache ('Comprehensive Doctrine of the Bohemian Language').

[24] Modern scholars disagree about whether the conservative revivalists were motivated by nationalism or considered contemporary spoken Czech unsuitable for formal, widespread use.

[40] It represents the raised alveolar non-sonorant trill (IPA: [r̝]), a sound somewhere between Czech r and ž (example: "řeka" (river)ⓘ),[41] and is present in Dvořák.

Strč prst skrz krk ("Stick [your] finger through [your] throat") is a well-known Czech tongue twister using syllabic consonants but no vowels.

[48] Parts of speech include adjectives, adverbs, numbers, interrogative words, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections.

[50] Negative statements are formed by adding the affix ne- to the main verb of a clause,[51] with one exception: je (he, she or it is) becomes není.

The following is a glossed example:[61] Chc-iwant-1SGnavštív-itvisit-INFuniversit-u,university-SG.ACC,naonkter-ouwhich-SG.F.ACCchod-íattend-3SGJan.John.SG.NOMChc-i navštív-it universit-u, na kter-ou chod-í Jan.want-1SG visit-INF university-SG.ACC, on which-SG.F.ACC attend-3SG John.SG.NOMI want to visit the university that John attends.In Czech, nouns and adjectives are declined into one of seven grammatical cases which indicate their function in a sentence, two numbers (singular and plural) and three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter).

[67] This is a glossed example of a sentence using several cases: Nes-lcarry-SG.M.PSTjs-embe-1.SGkrabic-ibox-SG.ACCdointodom-uhouse-SG.GENsewithsv-ýmown-SG.INSpřítel-em.friend-SG.INSNes-l js-em krabic-i do dom-u se sv-ým přítel-em.carry-SG.M.PST be-1.SG box-SG.ACC into house-SG.GEN with own-SG.INS friend-SG.INSI carried the box into the house with my friend.Czech distinguishes three genders—masculine, feminine, and neuter—and the masculine gender is subdivided into animate and inanimate.

Typical of a Slavic language, Czech cardinal numbers one through four allow the nouns and adjectives they modify to take any case, but numbers over five require subject and direct object noun phrases to be declined in the genitive plural instead of the nominative or accusative, and when used as subjects these phrases take singular verbs.

[73][74] Although Czech's grammatical numbers are singular and plural, several residuals of dual forms remain, such as the words dva ("two") and oba ("both"), which decline the same way.

Some nouns for paired body parts use a historical dual form to express plural in some cases: ruka (hand)—ruce (nominative); noha (leg)—nohama (instrumental), nohou (genitive/locative); oko (eye)—oči, and ucho (ear)—uši.

[76] Czech verbs agree with their subjects in person (first, second or third), number (singular or plural), and in constructions involving participles, which includes the past tense, also in gender.

Conversely, verbs describing immediate states of change—for example, otěhotnět (to become pregnant) and nadchnout se (to become enthusiastic)—have no imperfective aspect.

[96] The háček (ˇ) is used with certain letters to form new characters: š, ž, and č, as well as ň, ě, ř, ť, and ď (the latter five uncommon outside Czech).

Long u is usually written ú at the beginning of a word or morpheme (úroda, neúrodný) and ů elsewhere,[99] except for loanwords (skútr) or onomatopoeia (bú).

[102] Czech typographical features not associated with phonetics generally resemble those of most European languages that use the Latin script, including English.

Proper nouns, honorifics, and the first letters of quotations are capitalized, and punctuation is typical of other Latin European languages.

When writing a long number, spaces between every three digits, including those in decimal places, may be used for better orientation in handwritten texts.

It is usually defined as an interdialect used in common speech in Bohemia and western parts of Moravia (by about two thirds of all inhabitants of the Czech Republic).

Since the second half of the 20th century, Common Czech elements have also been spreading to regions previously unaffected, as a consequence of media influence.

[113] It is sometimes defined as a theoretical construct rather than an actual tool of colloquial communication, since in casual contexts, the non-standard interdialect is preferred.

[117] In addition, a prothetic v- is added to most words beginning o-, such as votevřít vokno (to open the window).

Increased travel and media availability to dialect-speaking populations has encouraged them to shift to (or add to their own dialect) Standard Czech.

[130] A 2015 study involving participants with a mean age of around 23 nonetheless concluded that there remained a high degree of mutual intelligibility between the two languages.

[134] Some loanwords have been restructured by folk etymology to resemble native Czech words (e.g. hřbitov, "graveyard" and listina, "list").