Common descent

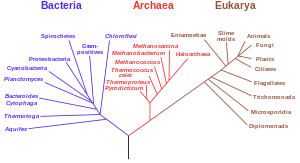

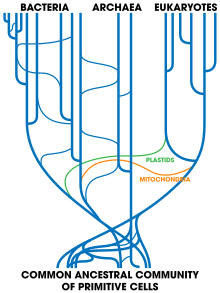

[8][9] All currently living organisms on Earth share a common genetic heritage, though the suggestion of substantial horizontal gene transfer during early evolution has led to questions about the monophyly (single ancestry) of life.

[10][11] Universal common descent through an evolutionary process was first proposed by the British naturalist Charles Darwin in the concluding sentence of his 1859 book On the Origin of Species: There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

[13] Later on, in the 1740s, the French mathematician Pierre Louis Maupertuis arrived at the idea that all organisms had a common ancestor, and had diverged through random variation and natural selection.

[16] In 1794, Charles Darwin's grandfather, Erasmus Darwin asked: [W]ould it be too bold to imagine, that in the great length of time, since the earth began to exist, perhaps millions of ages before the commencement of the history of mankind, would it be too bold to imagine, that all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament, which the great First Cause endued with animality, with the power of acquiring new parts attended with new propensities, directed by irritations, sensations, volitions, and associations; and thus possessing the faculty of continuing to improve by its own inherent activity, and of delivering down those improvements by generation to its posterity, world without end?

And in the subsequent edition,[19] he asserts rather, "We do not know all the possible transitional gradations between the simplest and the most perfect organs; it cannot be pretended that we know all the varied means of Distribution during the long lapse of years, or that we know how imperfect the Geological Record is.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the scientific community at large has accepted evolutionary descent as a historical reality since Darwin's time and considers it among the most reliably established and fundamentally important facts in all of science.

[22]All known forms of life are based on the same fundamental biochemical organization: genetic information encoded in DNA, transcribed into RNA, through the effect of protein- and RNA-enzymes, then translated into proteins by (highly similar) ribosomes, with ATP, NADPH and others as energy sources.

Richard Egel argues that in particular the hydrophobic (non-polar) side-chains are well organised, suggesting that these enabled the earliest organisms to create peptides with water-repelling regions able to support the essential electron exchange (redox) reactions for energy transfer.

Similarly, shared nucleotide sequences, especially where these are apparently neutral such as the positioning of introns and pseudogenes, provide strong evidence of common ancestry.

These similarities include the energy carrier adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and the fact that all amino acids found in proteins are left-handed.

In 2010, Douglas L. Theobald published a statistical analysis of available genetic data,[3] mapping them to phylogenetic trees, that gave "strong quantitative support, by a formal test, for the unity of life.

[3] However, biologists consider it very unlikely that completely unrelated proto-organisms could have exchanged genes, as their different coding mechanisms would have resulted only in garble rather than functioning systems.

Although such a universal common ancestor may have existed, such a complex entity is unlikely to have arisen spontaneously from non-life and thus a cell with a DNA genome cannot reasonably be regarded as the origin of life.