Concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.

The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach, cognitive science.

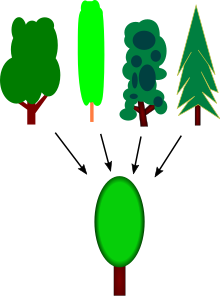

[7] When the mind makes a generalization such as the concept of tree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking.

A concept is instantiated (reified) by all of its actual or potential instances, whether these are things in the real world or other ideas.

Mental representations, in turn, are the building blocks of what are called propositional attitudes (colloquially understood as the stances or perspectives we take towards ideas, be it "believing", "doubting", "wondering", "accepting", etc.).

And these propositional attitudes, in turn, are the building blocks of our understanding of thoughts that populate everyday life, as well as folk psychology.

[9] In a physicalist theory of mind, a concept is a mental representation, which the brain uses to denote a class of things in the world.

[10][11] Concepts are mental representations that allow us to draw appropriate inferences about the type of entities we encounter in our everyday lives.

The abstraction from the day's hippocampal events and objects into cortical concepts is often considered to be the computation underlying (some stages of) sleep and dreaming.

[5] However, it is necessary at least to begin by understanding that the concept "dog" is philosophically distinct from the things in the world grouped by this concept—or the reference class or extension.

[5] The study of concepts and conceptual structure falls into the disciplines of linguistics, philosophy, psychology, and cognitive science.

[11] In the simplest terms, a concept is a name or label that regards or treats an abstraction as if it had concrete or material existence, such as a person, a place, or a thing.

Abstract ideas and knowledge domains such as freedom, equality, science, happiness, etc., are also symbolized by concepts.

He called these concepts categories, in the sense of the word that means predicate, attribute, characteristic, or quality.

For example, the view that numbers are Platonic objects was revived by Kurt Gödel as a result of certain puzzles that he took to arise from the phenomenological accounts.

[15] Gottlob Frege, founder of the analytic tradition in philosophy, famously argued for the analysis of language in terms of sense and reference.

For him, the sense of an expression in language describes a certain state of affairs in the world, namely, the way that some object is presented.

For example, the concepts of the derivative and the integral are not considered to refer to spatial or temporal perceptions of the external world of experience.

Neither are they related in any way to mysterious limits in which quantities are on the verge of nascence or evanescence, that is, coming into or going out of existence.

A set of features is considered sufficient if having all the parts required by the definition entails membership in the class.

[10] Another key part of this theory is that it obeys the law of the excluded middle, which means that there are no partial members of a class, you are either in or out.

[11] The classical theory persisted for so long unquestioned because it seemed intuitively correct and has great explanatory power.

There are six primary arguments[14] summarized as follows: Prototype theory came out of problems with the classical view of conceptual structure.

[14] Wittgenstein, Rosch, Mervis, Brent Berlin, Anglin, and Posner are a few of the key proponents and creators of this theory.

While the Classical theory requires an all-or-nothing membership in a group, prototypes allow for more fuzzy boundaries and are characterized by attributes.

[18] For example, a container holding mashed potatoes versus tea swayed people toward classifying them as a bowl and a cup, respectively.

There have been a number of experiments dealing with questionnaires asking participants to rate something according to the extent to which it belongs to a category.

It suggests that theories or mental understandings contribute more to what has membership to a group rather than weighted similarities, and a cohesive category is formed more by what makes sense to the perceiver.

Weights assigned to features have shown to fluctuate and vary depending on context and experimental task demonstrated by Tversky.