Square of opposition

The origin of the square can be traced back to Aristotle's tractate On Interpretation and its distinction between two oppositions: contradiction and contrariety.

Proposition O also takes the forms "Sometimes S is not P." and "A certain S is not P." (literally the Latin 'Quoddam S nōn est P.') **

Aristotle states (in chapters six and seven of the Peri hermēneias (Περὶ Ἑρμηνείας, Latin De Interpretatione, English 'On Interpretation')), that there are certain logical relationships between these four kinds of proposition.

A pair of an affirmative statement and its negation is, he calls, a 'contradiction' (in medieval Latin, contradictio).

The below relations, contrary, subcontrary, subalternation, and superalternation, do hold based on the traditional logic assumption that things stated as S (or things satisfying a statement S in modern logic) exist.

Another logical relation implied by this, though not mentioned explicitly by Aristotle, is 'alternation' (alternatio), consisting of 'subalternation' and 'superalternation'.

The Square of Oppositions was used for the categorical inferences described by the Greek philosopher Aristotle: conversion, obversion and contraposition.

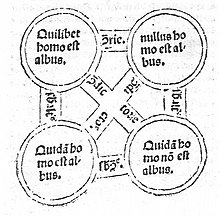

Each of those three types of categorical inference was applied to the four Boethian logical forms: A, E, I, and O. Subcontraries (I and O), which medieval logicians represented in the form 'quoddam A est B' (some particular A is B) and 'quoddam A non est B' (some particular A is not B) cannot both be false, since their universal contradictory statements (no A is B / every A is B) cannot both be true.

But Aristotelian logic requires that, necessarily, one of these statements (more generally 'some particular A is B' and 'some particular A is not B') is true, i.e., they cannot both be false.

[8] Abelard also points out that subcontraries containing subject terms denoting nothing, such as 'a man who is a stone', are both false.

He goes on to cite a medieval philosopher William of Moerbeke (1215–35 – c. 1286), And points to Boethius' translation of Aristotle's work as giving rise to the mistaken notion that the O form has existential import.

In the 19th century, George Boole (November 1815 – 8 December 1864) argued for requiring existential import on both terms in particular claims (I and O), but allowing all terms of universal claims (A and E) to lack existential import.

This decision made Venn diagrams particularly easy to use for term logic.

Gottlob Frege (8 November 1848 – 26 July 1925)'s Begriffsschrift also presents a square of oppositions, organised in an almost identical manner to the classical square, showing the contradictories, subalternates and contraries between four formulae constructed from universal quantification, negation and implication.

Algirdas Julien Greimas (9 March 1917 – 27 February 1992)' semiotic square was derived from Aristotle's work.

[14] The square of opposition has been extended to a logical hexagon which includes the relationships of six statements.

It was discovered independently by both Augustin Sesmat (April 7, 1885 – December 12, 1957) and Robert Blanché (1898–1975).

In modern mathematical logic, statements containing words "all", "some" and "no", can be stated in terms of set theory if we assume a set-like domain of discourse.

This also implies that AaB does not entail AiB, and some of the syllogisms mentioned above are not valid when there are no A's (

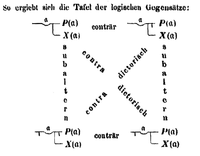

The conträr below is an erratum:

It should read subconträr .