Void (astronomy)

They were first discovered in 1978 in a pioneering study by Stephen Gregory and Laird A. Thompson at the Kitt Peak National Observatory.

Regions of higher density collapsed more rapidly under gravity, eventually resulting in the large-scale, foam-like structure or "cosmic web" of voids and galaxy filaments seen today.

[27] The first class consists of void finders that try to find empty regions of space based on local galaxy density.

[29] The third class is made of those finders which identify structures dynamically by using gravitationally unstable points in the distribution of dark matter.

The purpose for this change in definitions was presented by Lavaux and Wandelt in 2009 as a way to yield cosmic voids such that exact analytical calculations can be made on their dynamical and geometrical properties.

The simultaneous existence of the largest-known voids and galaxy clusters requires about 70% dark energy in the universe today, consistent with the latest data from the cosmic microwave background.

This has an effect on the size and depth distribution of voids, and is expected to make it possible with future astronomical surveys (e.g. the Euclid satellite) to measure the sum of the masses of all neutrino species by comparing the statistical properties of void samples to theoretical predictions.

This unique mix supports the biased galaxy formation picture predicted in Gaussian adiabatic cold dark matter models.

Such observations like the morphology-density correlation can help uncover new facets about how galaxies form and evolve on the large scale.

[41] On a more local scale, galaxies that reside in voids have differing morphological and spectral properties than those that are located in the walls.

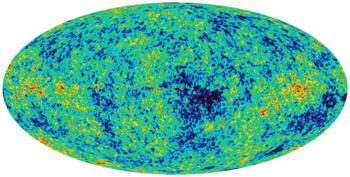

[43][44] Cold spots in the cosmic microwave background, such as the WMAP cold spot found by Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, could possibly be explained by an extremely large cosmic void that has a radius of ~120 Mpc, as long as the late integrated Sachs–Wolfe effect was accounted for in the possible solution.

Anomalies in CMB screenings are now being potentially explained through the existence of large voids located down the line-of-sight in which the cold spots lie.

[45] Although dark energy is currently the most popular explanation for the acceleration in the expansion of the universe, another theory elaborates on the possibility of our galaxy being part of a very large, not-so-underdense, cosmic void.

According to this theory, such an environment could naively lead to the demand for dark energy to solve the problem with the observed acceleration.

As more data has been released on this topic the chances of it being a realistic solution in place of the current ΛCDM interpretation has been largely diminished but not all together abandoned.

It is because of this unique feature that cosmic voids are useful laboratories to study the effects that gravitational clustering and growth rates have on local galaxies and structure when the cosmological parameters have different values from the outside universe.