Critical mass (sociodynamics)

The term "critical mass" is borrowed from nuclear physics, where it refers to the amount of a substance needed to sustain a chain reaction.

Recent technology research in platform ecosystems shows that apart from the quantitative notion of a “sufficient number”, critical mass is also influenced by qualitative properties such as reputation, interests, commitments, capabilities, goals, consensuses, and decisions, all of which are crucial in determining whether reciprocal behavior can be started to achieve sustainability to a commitment such as an idea, new technology, or innovation.

Critical mass is a concept used in a variety of contexts, including physics, group dynamics, politics, public opinion, and technology.

The concept of critical mass was originally created by game theorist Thomas Schelling and sociologist Mark Granovetter to explain the actions and behaviors of a wide range of people and phenomenon.

Finally, Herbert A. Simon's essay, "Bandwagon and underdog effects and the possibility of election predictions", published in 1954 in Public Opinion Quarterly,[9] has been cited as a predecessor to the concept we now know as critical mass.

Certain theories, such as Mancur Olson's Logic of Collective Action[10] or Garrett Hardin's Tragedy of the Commons,[11] work to help us understand why humans do or adopt certain things which are beneficial to them, or, more importantly, why they do not.

Oliver, Marwell, and Teixeira tackle this subject in relation to critical theory in a 1985 article published in the American Journal of Sociology.

By their definition, then, "critical mass" is the small segment of a societal system that does the work or action required to achieve the common good.

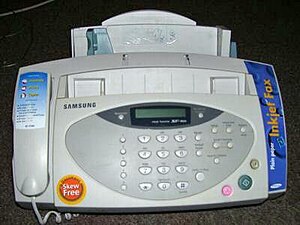

[19][20] While critical mass can be applied to many different aspects of sociodynamics, it becomes increasingly applicable to innovations in interactive media such as the telephone, fax, or email.

Thus, the increase of adopters and quickness to reach critical mass can therefore be faster and more intense with interactive media, as can the rate at which previous users discontinue their use.

Another proposition suggests that a media's ease of use and inexpensiveness, as well as its utilization of an "active notification capability" will help it achieve universal access.

Finally, Markus posits that interventions, both monetarily and otherwise, by governments, businesses, or groups of individuals will help a media reach its critical mass and achieve universal access.