Crystallization

An important feature of this step is that loose particles form layers at the crystal's surface and lodge themselves into open inconsistencies such as pores, cracks, etc.

Geological time scale process examples include: Human time scale process examples include: Crystal formation can be divided into two types, where the first type of crystals are composed of a cation and anion, also known as a salt, such as sodium acetate.

A typical laboratory technique for crystal formation is to dissolve the solid in a solution in which it is partially soluble, usually at high temperatures to obtain supersaturation.

For biological molecules in which the solvent channels continue to be present to retain the three dimensional structure intact, microbatch[2] crystallization under oil and vapor diffusion[3] have been the common methods.

Whereas most processes that yield more orderly results are achieved by applying heat, crystals usually form at lower temperatures – especially by supercooling.

However, the release of the heat of fusion during crystallization causes the entropy of the universe to increase, thus this principle remains unaltered.

Similarly, when the molten crystal is cooled, the molecules will return to their crystalline form once the temperature falls beyond the turning point.

The nature of the crystallization process is governed by both thermodynamic and kinetic factors, which can make it highly variable and difficult to control.

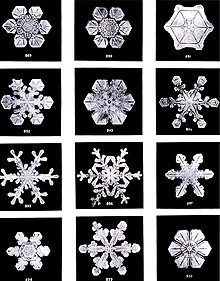

Factors such as impurity level, mixing regime, vessel design, and cooling profile can have a major impact on the size, number, and shape of crystals produced.

As mentioned above, a crystal is formed following a well-defined pattern, or structure, dictated by forces acting at the molecular level.

As a consequence, during its formation process the crystal is in an environment where the solute concentration reaches a certain critical value, before changing status.

Nucleation is the initiation of a phase change in a small region, such as the formation of a solid crystal from a liquid solution.

It is a consequence of rapid local fluctuations on a molecular scale in a homogeneous phase that is in a state of metastable equilibrium.

The benefits include the following:[6] The following model, although somewhat simplified, is often used to model secondary nucleation:[5] where Once the first small crystal, the nucleus, forms it acts as a convergence point (if unstable due to supersaturation) for molecules of solute touching – or adjacent to – the crystal so that it increases its own dimension in successive layers.

The supersaturated solute mass the original nucleus may capture in a time unit is called the growth rate expressed in kg/(m2*h), and is a constant specific to the process.

[8] Also, larger crystals have a smaller surface area to volume ratio, leading to a higher purity.

Some of the important factors influencing solubility are: So one may identify two main families of crystallization processes: This division is not really clear-cut, since hybrid systems exist, where cooling is performed through evaporation, thus obtaining at the same time a concentration of the solution.

An example of this crystallization process is the production of Glauber's salt, a crystalline form of sodium sulfate.

Assuming a saturated solution at 30 °C, by cooling it to 0 °C (note that this is possible thanks to the freezing-point depression), the precipitation of a mass of sulfate occurs corresponding to the change in solubility from 29% (equilibrium value at 30 °C) to approximately 4.5% (at 0 °C) – actually a larger crystal mass is precipitated, since sulfate entrains hydration water, and this has the side effect of increasing the final concentration.

Another option is to obtain, at an approximately constant temperature, the precipitation of the crystals by increasing the solute concentration above the solubility threshold.

[10] This can be achieved by a separation – to put it simply – of the crystals from the liquid mass, in order to manage the two flows in a different way.

The practical way is to perform a gravity settling to be able to extract (and possibly recycle separately) the (almost) clear liquid, while managing the mass flow around the crystallizer to obtain a precise slurry density elsewhere.

The DTB crystallizer (see images) has an internal circulator, typically an axial flow mixer – yellow – pushing upwards in a draft tube while outside the crystallizer there is a settling area in an annulus; in it the exhaust solution moves upwards at a very low velocity, so that large crystals settle – and return to the main circulation – while only the fines, below a given grain size are extracted and eventually destroyed by increasing or decreasing temperature, thus creating additional supersaturation.