Cuyahoga Valley National Park

It was the twelfth-most visited American national park in 2023, attracting nearly 2.9 million visitors, primarily due to its proximity to Cleveland and Akron.

[7][8] They had a democratic and egalitarian sociopolitical structure where leaders (sachem) consulted elders who advocated for the expectations of the people before decisions were made.

[9] The Lenapé were actively involved in long-distance trade networks and were highly skilled at creating goods and art such as pottery, stone weaponry, clothing, and baskets.

[14] As the Lenapé Nation was pushed west, ecological consistencies between present-day Pennsylvania and Ohio allowed them to continue similar agricultural, hunting, and fishing practices; however, as treaties and violent conflicts continued, the Lenapé were not permitted sufficient time to develop a relationship with land in the Ohio River Valley.

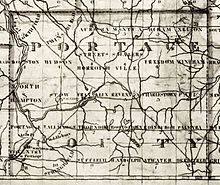

[18] These trade networks depended on waterways used by indigenous people through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: Portage Path was located in modern-day Summit County, Ohio.

[19]The Cuyahoga Valley is no longer inhabited by the Lenapé Nation primarily due to coercive legislative processes and numerous violent conflicts.

In 1805, 500,000 acres (200,000 ha) of land, including the present-day Cuyahoga Valley National Park, was ceded in the Treaty of Fort Industry with a promise of a thousand dollar annual payout to each Native Nation that lost land (the Wyandot, Ottawa, Objibwe, Munsee, Lenapé, Potawatomi, and Shawnee).

[12] The valley began providing recreation for urban dwellers in the 1870s when people came from nearby cities for carriage rides or leisure boat trips along the canal.

In 1929, the estate of Cleveland businessman Hayward Kendall donated 430 acres (0.7 sq mi; 1.7 km2) around the Ritchie Ledges[26] and a trust fund to the state of Ohio.

In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps built much of the park's infrastructure including the Happy Days Lodge and the shelters at Octagon, the Ledges, and Kendall Lake.

[29] Although the regional parks safeguarded certain places, by the 1960s local citizens feared that urban sprawl would overwhelm the Cuyahoga Valley's natural beauty.

Finally, on December 27, 1974, President Gerald Ford signed the bill establishing the Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area,[32] even as the administration recommended a veto because "The Cuyahoga Valley possesses no qualities which qualify it for inclusion in the National Park System" and the government was already providing funds for outdoor recreation.

[33] After Congress authorized the land acquisition, it was left under the direction of Superintendent William C. Birdsell of the National Park Service and the Army Corps of Engineers .

There was no comprehensive plan to guide the land acquisition program, so the responsibility of choosing whether homes were to be purchased or preserved was solely Birdsell's decision.

Birdsell's continually changing priorities frustrated local residents as land acquisition plans changed,[35] and his management style was criticized by the National Park Service's Midwest Regional Office during a 1978 operational evaluation report (OER), citing his poor human-resource management skills, low staff morale, and Birdsell's inability to delegate.

[36] The National Park Service acquired the 47-acre (0.1 sq mi; 0.2 km2) Krejci Dump in 1985 to include as part of the recreation area.

After the survey identified extremely toxic materials, the area was closed in 1986 and designated a superfund site under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980.

[37] Litigation was filed against potentially responsible parties: Ford, General Motors, Chrysler, 3M, Waste Management, Chevron, Kewanee Industries, and Federal Metals.

[45] Animals found in the park are animals typical throughout Ohio, including raccoons, muskrats, coyotes, skunks, red foxes, beavers, peregrine falcons, river otters, bald eagles, opossums, three species of moles, white-tailed deer, Canada geese, gray foxes, minks, great blue herons, and seven species of bats.

The plant hardiness zone at Boston Store Visitor Center is 6a with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of −6.5 °F (−21.4 °C).

[50] The park also features preserved and restored displays of 19th and early 20th century sustainable farming and rural living, most notably the Hale Farm and Village, while catering to contemporary cultural interests with art exhibits, outdoor concerts, and theater performances in venues such as Blossom Music Center and Kent State University's Porthouse Theatre.

Sections of the towpath trail outside of Cuyahoga Valley National Park are owned and maintained by various state and local agencies.

Seasonally, the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) allows visitors to travel along the towpath from Rockside Road to Akron, embarking or disembarking at any of the stops along the way.

Other streams have made routes into the Cuyahoga preglacial valley by cutting gorges with waterfalls such as those found along the Tinkers, Brandywine and Chippewa Creeks.

The moraine varies in width from 2–4 mi (3.2–6.4 km), and according to Leverett, "it is like a broad wave whose crest stands 20 to 50 feet above the border of the plain outside it."

Mastick's well was drilled in the Rockport Township to a depth of 527 ft (161 m), yielding 21,643 cubic feet (612.9 m3) of gas daily.

Pressures were 3–135 psi (21–931 kPa) flowing less than 20,000 cubic feet (570 m3) of gas daily, but was sufficient to furnish light for a house or two, and sometimes heat.

The house is a fine example of a Western Reserve home and features exhibits relating to architectural styles, construction techniques, and the Frazee family.