Cynodontia

'dog-teeth') is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event.

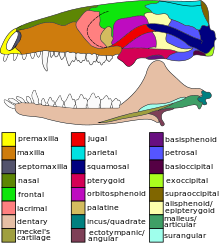

The temporal fenestrae were much larger than those of their ancestors, and the widening of the zygomatic arch in a more mammal-like skull would have allowed for more robust jaw musculature.

[4][5] In prozostrodontian cynodonts, the group that includes mammals, the foramina are replaced by a single large infraorbital foramen, which indicates that the face had become muscular and that whiskers would have been present.

These served to strengthen the torso and support abdominal and hindlimb musculature, aiding them in the development of an erect gait, but at the expense of prolonged pregnancy, forcing these animals to give birth to highly altricial young as in modern marsupials and monotremes.

[7][8] A specimen of Kayentatherium does indeed demonstrate that at least tritylodontids already had a fundamentally marsupial-like reproductive style, but produced much higher litters at around 38 perinates or possibly eggs.

[11] The largest known non-mammalian cynodont is Scalenodontoides, a traversodontid, which has been estimated to have a maximum skull length of approximately 617 millimetres (24.3 in) based on a fragmentary specimen.

The second is the herbivorous Tritylodontidae, which first appeared in the latest Triassic, which were abundant and diverse during the Jurassic, predominantly in the Northern Hemisphere, persisted into the Early Cretaceous (Barremian-Aptian) in Asia, at least until around 120 million years ago, as represented by Fossiomanus from China.

This caused air flow from the nostrils to travel to a position in the back of the mouth instead of directly through it, allowing cynodonts to chew and breathe at the same time.

[20] Robert Broom (1913) reranked Cynodontia as an infraorder, since retained by others, including Colbert and Kitching (1977), Carroll (1988), Gauthier et al. (1989), and Rubidge and Cristian Sidor (2001).

[22][23] Below is a cladogram from Ruta, Botha-Brink, Mitchell and Benton (2013) showing one hypothesis of cynodont relationships:[16] †Charassognathus †Dvinia †Procynosuchus †Cynosaurus †Galesaurus †Progalesaurus †Nanictosaurus †Thrinaxodon †Platycraniellus †Cynognathus †Diademodon †Beishanodon †Sinognathus †Trirachodon †Cricodon †Langbergia †Andescynodon †Pascualgnathus †Scalenodon †Luangwa †Traversodon †"Scalenodon" attridgei †Mandagomphodon †Nanogomphodon †Arctotraversodon †Boreogomphodon †Massetognathus †Dadadon †Santacruzodon †Menadon †Gomphodontosuchus †Protuberum †Exaeretodon †Scalenodontoides †Lumkuia †Ecteninion †Aleodon †Chiniquodon †Probainognathus †Trucidocynodon †Therioherpeton †Riograndia †Chaliminia †Elliotherium †Diarthrognathus †Pachygenelus †Brasilitherium †Brasilodon †Oligokyphus †Kayentatherium †Tritylodon †Beinotherium Mammalia †Sinoconodon †Morganucodon Non-mammalian cynodonts have been found in South America, India, Africa, Antarctica,[24] Asia,[25] Europe[26] and North America.