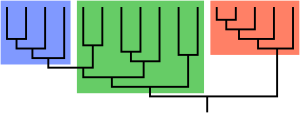

Polyphyly

[1] The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which are explained as a result of convergent evolution.

[6] In recent research, the concepts of monophyly, paraphyly, and polyphyly have been used in deducing key genes for barcoding of diverse groups of species.

[7] The term polyphyly, or polyphyletic, derives from the two Ancient Greek words πολύς (polús) 'many, a lot of', and φῦλον (phûlon) 'genus, species',[8][9] and refers to the fact that a polyphyletic group includes organisms (e.g., genera, species) arising from multiple ancestral sources.

By comparison, the term paraphyly, or paraphyletic, uses the ancient Greek preposition παρά (pará) 'beside, near',[8][9] and refers to the situation in which one or several monophyletic subgroups are left apart from all other descendants of a unique common ancestor.

[10] Species have a special status in systematics as being an observable feature of nature itself and as the basic unit of classification.