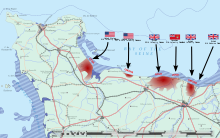

Normandy landings

Adolf Hitler placed Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in command of German forces and developing fortifications along the Atlantic Wall in anticipation of an invasion.

The men landed under heavy fire from gun emplacements overlooking the beaches, and the shore was mined and covered with obstacles such as wooden stakes, metal tripods, and barbed wire, making the work of the beach-clearing teams difficult and dangerous.

[16] In late May 1942, the Soviet Union and the United States made a joint announcement that a "... full understanding was reached with regard to the urgent tasks of creating a second front in Europe in 1942.

"[17] However, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill persuaded US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to postpone the promised invasion as, even with US help, the Allies did not have adequate forces for such an activity.

[26] A series of modified tanks, nicknamed Hobart's Funnies, dealt with specific requirements expected for the Normandy Campaign such as mine clearing, demolishing bunkers, and mobile bridging.

[30] Eventually, thirty-nine Allied divisions would be committed to the Battle of Normandy: twenty-two American, twelve British, three Canadian, one Polish, and one French, totalling over a million troops.

[26] To gain the air superiority needed to ensure a successful invasion, the Allies undertook a bombing campaign (codenamed Operation Pointblank) that targeted German aircraft production, fuel supplies, and airfields.

[42] In addition, on the night before the invasion, a small group of Special Air Service operators deployed dummy paratroopers over Le Havre and Isigny.

[42] As the Luftwaffe meteorological centre in Paris was predicting two weeks of stormy weather, many Wehrmacht commanders left their posts to attend war games in Rennes, and men in many units were given leave.

In addition to concrete gun emplacements at strategic points along the coast, he ordered wooden stakes, metal tripods, mines, and large anti-tank obstacles to be placed on the beaches to delay the approach of landing craft and impede the movement of tanks.

If the airports at Hamburg and Bremen could be taken by parachute units and the ports of these cities seized by small forces, invasion armies debarking from ships would, I feared, meet no resistance and would be occupying Berlin and all of Germany within a few days.

Geyr argued for a conventional doctrine: keeping the Panzer formations concentrated in a central position around Paris and Rouen and deploying them only when the main Allied beachhead had been identified.

[93][94] A 1965 report from the Counter-insurgency Information Analysis Center details the results of the French Resistance's sabotage efforts: "In the southeast, 52 locomotives were destroyed on 6 June and the railway line cut in more than 500 places.

After attacking, the German vessels turned away and fled east into a smoke screen that had been laid by the RAF to shield the fleet from the long-range battery at Le Havre.

To slow or eliminate the enemy's ability to organise and launch counter-attacks during this critical period, airborne operations were used to seize key objectives such as bridges, road crossings, and terrain features, particularly on the eastern and western flanks of the landing areas.

[117][115] Paratroops from 101st Airborne were dropped beginning around 01:30, tasked with controlling the causeways behind Utah Beach and destroying road and rail bridges over the Douve River.

[118] On the east side of the river, 75 per cent of the paratroopers landed in or near their drop zone, and within two hours they captured the important crossroads at Sainte-Mère-Église (the first town liberated in the invasion)[123] and began working to protect the western flank.

Lieutenant Colonel Terence Otway, in charge of the operation, decided to proceed regardless, as the emplacement had to be destroyed by 06:00 to prevent it firing on the invasion fleet and the troops arriving on Sword Beach.

The assistant commander of the 4th Infantry Division, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., the first senior officer ashore, made the decision to "start the war from right here," and ordered further landings to be re-routed.

[150][151] Pointe du Hoc, a prominent headland situated between Utah and Omaha, was assigned to two hundred men of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Rudder.

[160] For fear of hitting the landing craft, US bombers delayed releasing their loads and as a result most of the beach obstacles at Omaha remained undamaged when the men came ashore.

[167] High winds made conditions difficult for the landing craft, and the amphibious DD tanks were released close to shore or directly on the beach instead of further out as planned.

[169] Aerial attacks had failed to hit the Le Hamel strongpoint, which had its embrasure facing east to provide enfilade fire along the beach and had a thick concrete wall on the seaward side.

[170] Its 75 mm gun continued to do damage until 16:00, when an Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers (AVRE) tank fired a large demolition charge into its rear entrance.

[175] Company Sergeant Major Stanley Hollis received the only Victoria Cross awarded on D-Day for his actions including attacking two pillboxes at the Mont Fleury high point.

At Mike Beach on the western flank, a large crater was filled using an abandoned AVRE tank and several rolls of fascine, which were then covered by a temporary bridge.

[180] Major German strongpoints with 75 mm guns, machine-gun nests, concrete fortifications, barbed wire, and mines were located at Courseulles-sur-Mer, St Aubin-sur-Mer, and Bernières-sur-Mer.

[192] The 2nd Battalion, King's Shropshire Light Infantry began advancing to Caen on foot, coming within a few kilometres of the town, but had to withdraw due to lack of armour support.

German preparations along the Atlantic Wall were only partially finished; shortly before D-Day Rommel reported that construction was only 18 per cent complete in some areas as resources were diverted elsewhere.

[207] Some of the opening bombardment was off-target or not concentrated enough to have any impact,[161] but the specialised armour worked well except on Omaha (where most of it had been lost at sea), providing close artillery support for the troops as they disembarked onto the beaches.