RNA polymerase

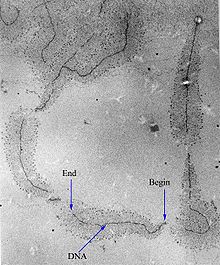

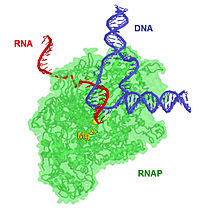

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the double-stranded DNA so that one strand of the exposed nucleotides can be used as a template for the synthesis of RNA, a process called transcription.

The former is found in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes alike, sharing a similar core structure and mechanism.

Eukaryotes have multiple types of nuclear RNAP, each responsible for synthesis of a distinct subset of RNA: The 2006 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Roger D. Kornberg for creating detailed molecular images of RNA polymerase during various stages of the transcription process.

[5][6] The core RNA polymerase complex forms a "crab claw" or "clamp-jaw" structure with an internal channel running along the full length.

[9][10] Control of the process of gene transcription affects patterns of gene expression and, thereby, allows a cell to adapt to a changing environment, perform specialized roles within an organism, and maintain basic metabolic processes necessary for survival.

RNAP will preferentially release its RNA transcript at specific DNA sequences encoded at the end of genes, which are known as terminators.

Such specific interactions explain why RNAP prefers to start transcripts with ATP (followed by GTP, UTP, and then CTP).

However these stabilizing contacts inhibit the enzyme's ability to access DNA further downstream and thus the synthesis of the full-length product.

Once the DNA-RNA heteroduplex is long enough (~10 bp), RNA polymerase releases its upstream contacts and effectively achieves the promoter escape transition into the elongation phase.

RNA polymerase can also relieve the stress by releasing its downstream contacts, arresting transcription.

The paused transcribing complex has two options: (1) release the nascent transcript and begin anew at the promoter or (2) reestablish a new 3′-OH on the nascent transcript at the active site via RNA polymerase's catalytic activity and recommence DNA scrunching to achieve promoter escape.

The extent of abortive initiation depends on the presence of transcription factors and the strength of the promoter contacts.

[18] Aspartyl (asp) residues in the RNAP will hold on to Mg2+ ions, which will, in turn, coordinate the phosphates of the ribonucleotides.

[19] The overall reaction equation is: Unlike the proofreading mechanisms of DNA polymerase those of RNAP have only recently been investigated.

[24] Given that DNA and RNA polymerases both carry out template-dependent nucleotide polymerization, it might be expected that the two types of enzymes would be structurally related.

Sigma reduces the affinity of RNAP for nonspecific DNA while increasing specificity for promoters, allowing transcription to initiate at correct sites.

Eukaryotes have multiple types of nuclear RNAP, each responsible for synthesis of a distinct subset of RNA.

Due to its bacterial origin, the organization of PEP resembles that of current bacterial RNA polymerases: It is encoded by the RPOA, RPOB, RPOC1 and RPOC2 genes on the plastome, which as proteins form the core subunits of PEP, respectively named α, β, β′ and β″.

[35] Similar to the RNA polymerase in E. coli, PEP requires the presence of sigma (σ) factors for the recognition of its promoters, containing the -10 and -35 motifs.

[36] Despite the many commonalities between plant organellar and bacterial RNA polymerases and their structure, PEP additionally requires the association of a number of nuclear encoded proteins, termed PAPs (PEP-associated proteins), which form essential components that are closely associated with the PEP complex in plants.

[8] Orthopoxviruses and some other nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses synthesize RNA using a virally encoded multi-subunit RNAP.

[2] B. subtilis prophage SPβ uses YonO, a homolog of the β+β′ subunits of msRNAPs to form a monomeric (both barrels on the same chain) RNAP distinct from the usual "right hand" ssRNAP.

It probably diverged very long ago from the canonical five-unit msRNAP, before the time of the last universal common ancestor.

[50] By this time, one half of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Medicine had been awarded to Severo Ochoa for the discovery of what was believed to be RNAP,[51] but instead turned out to be polynucleotide phosphorylase.