Enzyme catalysis

Enzymes often also incorporate non-protein components, such as metal ions or specialized organic molecules known as cofactor (e.g. adenosine triphosphate).

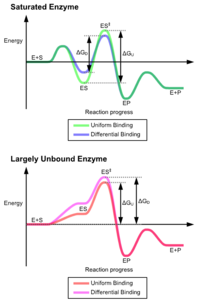

The reduction of activation energy (Ea) increases the fraction of reactant molecules that can overcome this barrier and form the product.

The advantages of the induced fit mechanism arise due to the stabilizing effect of strong enzyme binding.

[5] These effects have led to most proteins using the differential binding mechanism to reduce the energy of activation, so most substrates have high affinity for the enzyme while in the transition state.

Induced fit may be beneficial to the fidelity of molecular recognition in the presence of competition and noise via the conformational proofreading mechanism.

[6] These conformational changes also bring catalytic residues in the active site close to the chemical bonds in the substrate that will be altered in the reaction.

Often such theoretical effective concentrations are unphysical and impossible to realize in reality – which is a testament to the great catalytic power of many enzymes, with massive rate increases over the uncatalyzed state.

[7][8][9] Also, the original entropic proposal[10] has been found to largely overestimate the contribution of orientation entropy to catalysis.

Cystine and Histidine are very commonly involved, since they both have a pKa close to neutral pH and can therefore both accept and donate protons.

pKa can also be influenced significantly by the surrounding environment, to the extent that residues which are basic in solution may act as proton donors, and vice versa.

Systematic computer simulation studies established that electrostatic effects give, by far, the largest contribution to catalysis.

[16] In particular, it has been found that enzyme provides an environment which is more polar than water, and that the ionic transition states are stabilized by fixed dipoles.

[19] Binding of substrate usually excludes water from the active site, thereby lowering the local dielectric constant to that of an organic solvent.

In addition, studies have shown that the charge distributions about the active sites are arranged so as to stabilize the transition states of the catalyzed reactions.

This mechanism is utilised by the catalytic triad of enzymes such as proteases like chymotrypsin and trypsin, where an acyl-enzyme intermediate is formed.

An alternative mechanism is schiff base formation using the free amine from a lysine residue, as seen in the enzyme aldolase during glycolysis.

Some enzymes utilize non-amino acid cofactors such as pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) or thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) to form covalent intermediates with reactant molecules.

[20][21] Such covalent intermediates function to reduce the energy of later transition states, similar to how covalent intermediates formed with active site amino acid residues allow stabilization, but the capabilities of cofactors allow enzymes to carryout reactions that amino acid side residues alone could not.

A true proposal of a covalent catalysis (where the barrier is lower than the corresponding barrier in solution) would require, for example, a partial covalent bond to the transition state by an enzyme group (e.g., a very strong hydrogen bond), and such effects do not contribute significantly to catalysis.

[27] This is the principal effect of induced fit binding, where the affinity of the enzyme to the transition state is greater than to the substrate itself.

This approach as idea had formerly proposed relying on the hypothetical extremely high enzymatic conversions (catalytically perfect enzyme).

[40] The crucial point for the verification of the present approach is that the catalyst must be a complex of the enzyme with the transfer group of the reaction.

Consider the reaction of peptide bond hydrolysis catalyzed by a pure protein α-chymotrypsin (an enzyme acting without a cofactor), which is a well-studied member of the serine proteases family, see.

The final step of ATP hydrolysis in skeletal muscle is the product release caused by the association of myosin heads with actin.

[42] The closing of the actin-binding cleft during the association reaction is structurally coupled with the opening of the nucleotide-binding pocket on the myosin active site.

Trypsin (EC 3.4.21.4) is a serine protease that cleaves protein substrates after lysine or arginine residues using a catalytic triad to perform covalent catalysis, and an oxyanion hole to stabilise charge-buildup on the transition states.