Enzyme kinetics

An enzyme (E) is a protein molecule that serves as a biological catalyst to facilitate and accelerate a chemical reaction in the body.

For example, the structure can suggest how substrates and products bind during catalysis; what changes occur during the reaction; and even the role of particular amino acid residues in the mechanism.

[3] An analogous approach is to use mass spectrometry to monitor the incorporation or release of stable isotopes as the substrate is converted into product.

The enzyme produces product at an initial rate that is approximately linear for a short period after the start of the reaction.

To measure the initial (and maximal) rate, enzyme assays are typically carried out while the reaction has progressed only a few percent towards total completion.

However, equipment for rapidly mixing liquids allows fast kinetic measurements at initial rates of less than one second.

This can only be achieved however if one recognises the problem associated with the use of Euler's number in the description of first order chemical kinetics.

[13] In 1983 Stuart Beal (and also independently Santiago Schnell and Claudio Mendoza in 1997) derived a closed form solution for the time course kinetics analysis of the Michaelis-Menten mechanism.

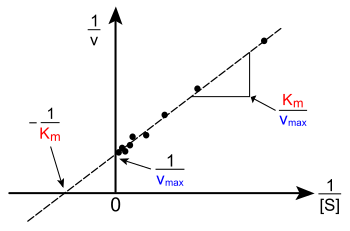

More generally, the Lineweaver–Burk plot skews the importance of measurements taken at low substrate concentrations and, thus, can yield inaccurate estimates of Vmax and KM.

In general, data normalisation can help diminish the amount of experimental work and can increase the reliability of the output, and is suitable for both graphical and numerical analysis.

The kinetic constants defined above, KM and Vmax, are critical to attempts to understand how enzymes work together to control metabolism.

Alternatively, one useful simplification of the metabolic modelling problem is to ignore the underlying enzyme kinetics and only rely on information about the reaction network's stoichiometry, a technique called flux balance analysis.

[28] The following links show short animations of the ternary-complex mechanisms of the enzymes dihydrofolate reductase[β] and DNA polymerase[γ].

In such mechanisms, substrate A binds, changes the enzyme to E* by, for example, transferring a chemical group to the active site, and is then released.

Enzymes with substituted-enzyme mechanisms include some oxidoreductases such as thioredoxin peroxidase,[30] transferases such as acylneuraminate cytidylyltransferase[31] and serine proteases such as trypsin and chymotrypsin.

Positive cooperativity makes enzymes much more sensitive to [S] and their activities can show large changes over a narrow range of substrate concentration.

Kinetic measurements taken under various solution conditions or on slightly modified enzymes or substrates often shed light on this chemical mechanism, as they reveal the rate-determining step or intermediates in the reaction.

For example, it is sometimes difficult to discern the origin of an oxygen atom in the final product; since it may have come from water or from part of the substrate.

[46] The chemical mechanism can also be elucidated by examining the kinetics and isotope effects under different pH conditions,[47] by altering the metal ions or other bound cofactors,[48] by site-directed mutagenesis of conserved amino acid residues, or by studying the behaviour of the enzyme in the presence of analogues of the substrate(s).

The binding of an inhibitor and its effect on the enzymatic activity are two distinctly different things, another problem the traditional equations fail to acknowledge.

To demonstrate the relationship the following rearrangement can be made: Adding zero to the bottom ([I]-[I]) Dividing by [I]+Ki This notation demonstrates that similar to the Michaelis–Menten equation, where the rate of reaction depends on the percent of the enzyme population interacting with substrate, the effect of the inhibitor is a result of the percent of the enzyme population interacting with inhibitor.

To account for this the equation can be easily modified to allow for different degrees of inhibition by including a delta Vmax term.

or This term can then define the residual enzymatic activity present when the inhibitor is interacting with individual enzymes in the population.

These conformational changes also bring catalytic residues in the active site close to the chemical bonds in the substrate that will be altered in the reaction.

Alternatively, the observation of a strong pH effect on Vmax but not KM might indicate that a residue in the active site needs to be in a particular ionisation state for catalysis to occur.

In 1902 Victor Henri proposed a quantitative theory of enzyme kinetics,[56] but at the time the experimental significance of the hydrogen ion concentration was not yet recognized.

After Peter Lauritz Sørensen had defined the logarithmic pH-scale and introduced the concept of buffering in 1909[57] the German chemist Leonor Michaelis and Dr. Maud Leonora Menten (a postdoctoral researcher in Michaelis's lab at the time) repeated Henri's experiments and confirmed his equation, which is now generally referred to as Michaelis-Menten kinetics (sometimes also Henri-Michaelis-Menten kinetics).

B. S. Haldane, who derived kinetic equations that are still widely considered today a starting point in modeling enzymatic activity.

This can be modeled by introducing several Michaelis-Menten pathways that are connected with fluctuating rates,[60][61][62] which is a mathematical extension of the basic Michaelis Menten mechanism.

ENZO allows rapid evaluation of rival reaction schemes and can be used for routine tests in enzyme kinetics.