Enzyme inhibitor

A low concentration of the enzyme inhibitor reduces the risk for liver and kidney damage and other adverse drug reactions in humans.

Enzyme inhibitors are a chemically diverse set of substances that range in size from organic small molecules to macromolecular proteins.

This provides a negative feedback loop that prevents over production of metabolites and thus maintains cellular homeostasis (steady internal conditions).

The most prominent example are serpins (serine protease inhibitors) which are produced by animals to protect against inappropriate enzyme activation and by plants to prevent predation.

Vmax will decrease due to the inability for the reaction to proceed as efficiently, but Km will remain the same as the actual binding of the substrate, by definition, will still function properly.

[24]: 6 In the classic Michaelis-Menten scheme (shown in the "inhibition mechanism schematic" diagram), an enzyme (E) binds to its substrate (S) to form the enzyme–substrate complex ES.

[31] However, the other dissociation constant Ki' is difficult to measure directly, since the enzyme-substrate complex is short-lived and undergoing a chemical reaction to form the product.

Hence, Ki' is usually measured indirectly, by observing the enzyme activity under various substrate and inhibitor concentrations, and fitting the data via nonlinear regression[32] to a modified Michaelis–Menten equation.

The effects of different types of reversible enzyme inhibitors on enzymatic activity can be visualised using graphical representations of the Michaelis–Menten equation, such as Lineweaver–Burk, Eadie-Hofstee or Hanes-Woolf plots.

The true value of Ki can be obtained through more complex analysis of the on (kon) and off (koff) rate constants for inhibitor association with kinetics similar to irreversible inhibition.

[38] Here the subnanomolar dissociation constant (KD) of TGDDF was greater than predicted presumably due to entropic advantages gained and/or positive interactions acquired through the atoms linking the components.

MAIs have also been observed to be produced in cells by reactions of pro-drugs such as isoniazid[39] or enzyme inhibitor ligands (for example, PTC124)[40] with cellular cofactors such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) respectively.

[46] This ensures that the inhibitor exploits the transition state stabilising effect of the enzyme, resulting in a better binding affinity (lower Ki) than substrate-based designs.

[51] Irreversible inhibitors often contain reactive functional groups such as nitrogen mustards, aldehydes, haloalkanes, alkenes, Michael acceptors, phenyl sulfonates, or fluorophosphonates.

Instead, kobs/[I] values are used,[56] where kobs is the observed pseudo-first order rate of inactivation (obtained by plotting the log of % activity versus time) and [I] is the concentration of inhibitor.

The binding and inactivation steps of this reaction are investigated by incubating the enzyme with inhibitor and assaying the amount of activity remaining over time.

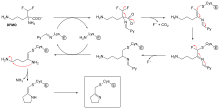

[69] An example is the inhibitor of polyamine biosynthesis, α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), which is an analogue of the amino acid ornithine, and is used to treat African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness).

However, this decarboxylation reaction is followed by the elimination of a fluorine atom, which converts this catalytic intermediate into a conjugated imine, a highly electrophilic species.

For example, in the figure showing trypanothione reductase from the human protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, two molecules of an inhibitor called quinacrine mustard are bound in its active site.

[3][1] In addition, naturally produced poisons are often enzyme inhibitors that have evolved for use as toxic agents against predators, prey, and competing organisms.

[80] Animals and plants have evolved to synthesise a vast array of poisonous products including secondary metabolites,[81] peptides and proteins[82] that can act as inhibitors.

For example, paclitaxel (taxol), an organic molecule found in the Pacific yew tree, binds tightly to tubulin dimers and inhibits their assembly into microtubules in the cytoskeleton.

[84] Many natural poisons act as neurotoxins that can cause paralysis leading to death and function for defence against predators or in hunting and capturing prey.

[86] An example of a neurotoxin are the glycoalkaloids, from the plant species in the family Solanaceae (includes potato, tomato and eggplant), that are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

[89] This toxin can contaminate water supplies after algal blooms and is a known carcinogen that can also cause acute liver haemorrhage and death at higher doses.

[98] An example of the structural similarity of some inhibitors to the substrates of the enzymes they target is seen in the figure comparing the drug methotrexate to folic acid.

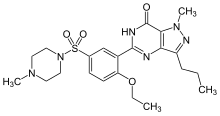

[100] This compound is a potent inhibitor of cGMP specific phosphodiesterase type 5, the enzyme that degrades the signalling molecule cyclic guanosine monophosphate.

[101] This signalling molecule triggers smooth muscle relaxation and allows blood flow into the corpus cavernosum, which causes an erection.

[124] The first general method is rational drug design based on mimicking the transition state of the chemical reaction catalysed by the enzyme.

[128] Complementary approaches that can provide new starting points for inhibitors include fragment-based lead discovery[129] and DNA Encoded Chemical Libraries (DEL).

![2D plots of 1/[S] concentration (x-axis) and 1/V (y-axis) demonstrating that as inhibitor concentration is changed, competitive inhibitor lines intersect at a single point on the y-axis, non-competitive inhibitors intersect at the x-axis, and mixed inhibitors intersect a point that is on neither axis](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/ba/Inhibition_diagrams-1-.png/220px-Inhibition_diagrams-1-.png)