Masters of the Universe (book)

Modern neoliberalism, according to Jones, is associated with economic liberalism, monetarism, and a staunch support of free market capitalism, and advocates political policies of deregulation, privatization, and other market-based reforms.

In the first, lasting from roughly 1920 until 1950, he details how early European neoliberal thinkers like Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, and Karl Popper, motivated by expanding government and later the rise of totalitarian regimes in Europe during World War II, developed critiques of "collectivism", which to them included British social democracy and American New Deal liberalism.

[3] "Neoliberalism was a radical form of individualism that was first generated before World War II in reaction to New Liberalism, Progressivism, the New Deal, and the onset of Nazi and communist totalitarianism.

[3]: 22 Keynesianism, developed by economist John Maynard Keynes and motivated by the widespread unemployment during the Great Depression, viewed government intervention in the economy as a means to alleviate economic downturns and achieve full employment.

[3]: 24 Neoliberalism, promoted by economists like Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Ludwig von Mises, and arising out of fears of totalitarian regimes like the Nazis, Soviet communists, and Italian fascists, viewed increasing government intervention as a threat to economic and political freedom.

[3]: 134 The locus of neoliberal thought shifted from Europe to the United States, with the American intellectuals Milton Friedman and George Stigler, as well as the larger Chicago school of economics they were a part of, becoming increasingly influential.

[4] The society set out to develop a neoliberal alternative to, on the one hand, the laissez-faire economic consensus that had collapsed with the Great Depression and, on the other, New Deal liberalism and British social democracy, collectivist trends which they believed posed a threat to individual freedom.

[3]: 33 Popper, in his book The Open Society and its Enemies, criticized thinkers from Plato to Karl Marx for valuing the collective over the individual and derided teleological historicism (a theory which holds that history unfolds inexorably according to universal laws) as a threat to individualism—which he believed underpins Western civilization—because it reduces the individual to "a cog in the machine" of history and empowers governments to engage in the sorts of "Utopian engineering" that has motivated communists, socialists, and Nazis.

[3]: 49–57 Hayek, in his book The Road to Serfdom, argued effective central planning was impossible because no individual or group could ever possess the requisite knowledge to direct the economic activity of millions of people.

[3]: 134 During this time, the locus of neoliberal thought shifted from Europe to America, with the American economist Milton Friedman becoming its most influential proponent—its "beating heart", as Jones describes it.

[3]: 345, 116 Neoliberals of the era emphasized the need to recover "lost truths" from classical liberalism, including the value of individual liberty, the invisible hand of the free market, and the virtues of limited government.

[3]: 101 By the 1960s, Jones contends, neoliberal thought had established a "distinct and coherent identity" centered around "individual liberty, free markets, spontaneous order, the price mechanism, competition, consumerism, deregulation, and rational self-interest".

A key point of Capitalism and Freedom, according to Jones, was outlining government failure, including in the areas of railroad regulation, labor law, monetary reform, agriculture, public housing, social security legislation, foreign aid, urban redevelopment, and income tax.

Jones sums it up as such: "Friedman's monetarist analysis and market solutions grabbed people's attention as a ready-made and plausible alternative strategy [to Keynesianism] when the economy began to unravel [in the 1970s] under the weight of stagflation".

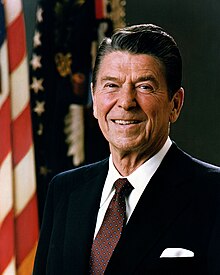

In particular, the Heritage Foundation had a significant influence on US president Ronald Reagan—claiming on its website that nearly two-thirds of the proposals they suggested to him in their policy guide Mandate for Leadership were implemented[6]—while the Adam Smith Institute had appreciable sway with the Thatcher government.

[3]: 140 This union, which Jones largely credits William F. Buckley Jr. for achieving, led to the growth of a conservative establishment that would, after decades of decline, rival its liberal opponents.

The assumption that there was a relatively simple and manipulable trade-off between inflation and employment, the famous Phillips Curve...proved to be a dangerous illusion...In both Britain and the United States, the appearance of stagflation...meant that governments felt forced to change course.

[3]: 219–220 As Jones describes it: "the late 1960s and early 1970s brought a succession of economic shocks that undermined the postwar international monetary system and pushed the world economy into stormy waters.

The final stage in the shift in economic strategy in Britain and the United States, the reason neoliberal ideas found a receptive audience, was the force of these events."

However, their approaches were examples of "governments of the left who accept[ed] the logic of the technical insights of Friedman and Stigler in terms of macroeconomic strategy or deregulation without also importing their neoliberal philosophies".

[3]: 249 Jones suggests that "perhaps the single most important economic policy decision made by Carter was his appointment of Paul Volcker in August 1979 to replace [George William] Miller as chairman of the Federal Reserve".

[9] Jones argues that the Reagan administration "followed neoliberal principles influenced particularly by the ideas of Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, George Stigler, and Pat Buchanan".

[3]: 263 Jones contends that "the key early battle for the Conservative government had been driving through a tough slew of measures to bring the deficit under control and create the conditions for economic recovery in the famous budget of 1981".

Jones places "the major differences, and the real departure in economic terms, between the Callaghan government and the Conservatives lay in their radicalization of microeconomic policy through various market-based supply-side reforms and their importation of market mechanisms into public service provision".

[3]: 332 He argues that this ultimately had mixed effects: "Some of the most powerful insights of [neoliberal] thinkers did help to address pressing social and economic issues by increasing homeownership or stabilizing persistently high inflation.

The Economist praised the book as a "bold biography of a great idea", describing it as a "novel and comprehensive history of neoliberalism" that, while "a little thin on character sketches and economics", is a "strong work" by a "fair and nuanced writer".

[15] Alejandro Chafuen, former president of the Atlas Economic Research Foundation and member of the Mont Pelerin Society, writes in Forbes that he appreciates that the author's "lengthy exposition of the views shared by these outstanding economists (Friedman, Hayek, and Mises) might encourage many to pay attention to their works".

[17] Glenn C. Altschuler, writing in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, states that the author "draws on extensive archival research and interviews with politicians, policy-makers and intellectuals to provide a lucid, richly detailed examination of the evolution of the free-market ideology since the end of World War II".

[19] Daniel Ben-Ami, writing in Financial Times, praised the book as "clearly written and relevant to a wide audience", noting it "incorporates a wealth of primary material", although he states Jones "fails to capture fully the failures or successes of neoliberal thought".

[21] Kenneth Minogue, writing for The Wall Street Journal, claims that, while the book "has intelligent things to say", its "historical virtues are compromised by more adjectival attitudinizing than a chronicler of history should allow himself"; for instance, "free-market ideas are characterized as 'aggressive,' 'relentless' and 'uncritical,' culminating in the description of market enthusiasm as a 'holy grail' and the use of a variety of religious metaphors designed to suggest that it is irrational".