2008 financial crisis

As demand and prices continued to fall, the financial contagion spread to global credit markets by August 2007, and central banks began injecting liquidity.

The Fed began a program of quantitative easing by buying treasury bonds and other assets, such as MBS, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, signed in February 2009 by newly elected President Barack Obama, included a range of measures intended to preserve existing jobs and create new ones.

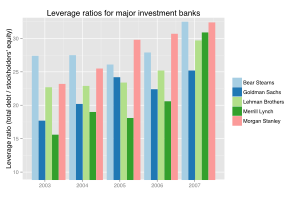

The de-leveraging of financial institutions, as assets were sold to pay back obligations that could not be refinanced in frozen credit markets, further accelerated the solvency crisis and caused a decrease in international trade.

[50] Alistair Darling, the U.K.'s Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time of the crisis, stated in 2018 that Britain came within hours of "a breakdown of law and order" the day that Royal Bank of Scotland was bailed-out.

The twenty largest economies contributing to global GDP (PPP) growth (2007–2017)[217] The expansion of central bank lending in response to the crisis was not confined to the Federal Reserve's provision of aid to individual financial institutions.

The Federal Reserve has also conducted several innovative lending programs to improve liquidity and strengthen different financial institutions and markets, such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

In his dissent to the majority report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, conservative American Enterprise Institute fellow Peter J. Wallison[267] stated his belief that the roots of the financial crisis can be traced directly and primarily to affordable housing policies initiated by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in the 1990s and to massive risky loan purchases by government-sponsored entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

[269][270] The hearings never resulted in new legislation or formal investigation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as many of the committee members refused to accept the report and instead rebuked OFHEO for their attempt at regulation.

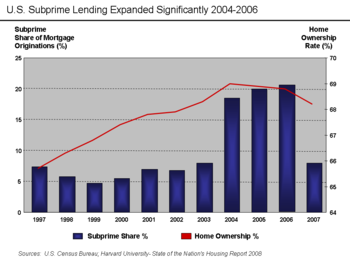

They contend that there were two, connected causes to the crisis: the relaxation of underwriting standards in 1995 and the ultra-low interest rates initiated by the Federal Reserve after the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001.

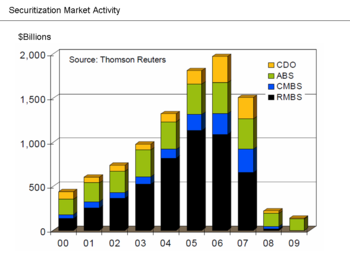

Essentially, investment banks and hedge funds used financial innovation to enable large wagers to be made, far beyond the actual value of the underlying mortgage loans, using derivatives called credit default swaps, collateralized debt obligations and synthetic CDOs.

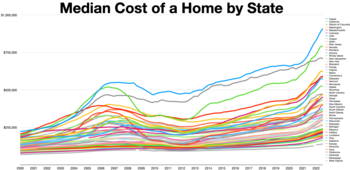

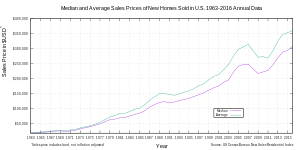

[293] This housing bubble resulted in many homeowners refinancing their homes at lower interest rates, or financing consumer spending by taking out second mortgages secured by the price appreciation.

In a Peabody Award-winning program, NPR correspondents argued that a "Giant Pool of Money" (represented by $70 trillion in worldwide fixed income investments) sought higher yields than those offered by U.S. Treasury bonds early in the decade.

[294] The collateralized debt obligation in particular enabled financial institutions to obtain investor funds to finance subprime and other lending, extending or increasing the housing bubble and generating large fees.

Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke explained how trade deficits required the U.S. to borrow money from abroad, in the process bidding up bond prices and lowering interest rates.

[327] A 2012 OECD study[328] suggest that bank regulation based on the Basel accords encourage unconventional business practices and contributed to or even reinforced the financial crisis.

Lehman Brothers went bankrupt and was liquidated, Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch were sold at fire-sale prices, and Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley became commercial banks, subjecting themselves to more stringent regulation.

Economist Hyman Minsky also described a "paradox of deleveraging" as financial institutions that have too much leverage (debt relative to equity) cannot all de-leverage simultaneously without significant declines in the value of their assets.

[349] In April 2009, Federal Reserve vice-chair Janet Yellen discussed these paradoxes: Once this massive credit crunch hit, it didn't take long before we were in a recession.

With increasing distance from the underlying asset these actors relied more and more on indirect information (including FICO scores on creditworthiness, appraisals and due diligence checks by third party organizations, and most importantly the computer models of rating agencies and risk management desks).

"[360] Mortgage risks were underestimated by almost all institutions in the chain from originator to investor by underweighting the possibility of falling housing prices based on historical trends of the past 50 years.

U.S. taxpayers provided over $180 billion in government loans and investments in AIG during 2008 and early 2009, through which the money flowed to various counterparties to CDS transactions, including many large global financial institutions.

He described the significance of these entities: In early 2007, asset-backed commercial paper conduits, in structured investment vehicles, in auction-rate preferred securities, tender option bonds and variable rate demand notes, had a combined asset size of roughly $2.2 trillion.

[376]Economist Paul Krugman, laureate of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, described the run on the shadow banking system as the "core of what happened" to cause the crisis.

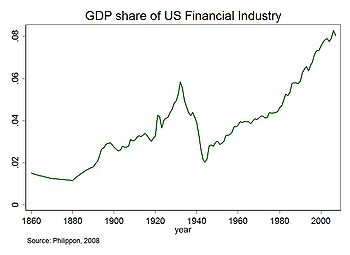

[382] John Bellamy Foster, a political economy analyst and editor of the Monthly Review, believed that the decrease in GDP growth rates since the early 1970s is due to increasing market saturation.

[383] Marxian economics followers Andrew Kliman, Michael Roberts, and Guglielmo Carchedi, in contradistinction to the Monthly Review school represented by Foster, pointed to capitalism's long-term tendency of the rate of profit to fall as the underlying cause of crises generally.

[384] In 2005 book, The Battle for the Soul of Capitalism, John C. Bogle wrote that "Corporate America went astray largely because the power of managers went virtually unchecked by our gatekeepers for far too long".

[401] Rajan argued that financial sector managers were encouraged to "take risks that generate severe adverse consequences with small probability but, in return, offer generous compensation the rest of the time.

"[405] Popular articles published in the mass media have led the general public to believe that the majority of economists have failed in their obligation to predict the financial crisis.

For example, an article in The New York Times noted that economist Nouriel Roubini warned of such crisis as early as September 2006, and stated that the profession of economics is bad at predicting recessions.

[412] Initially the companies affected were those directly involved in home construction and mortgage lending such as Northern Rock and Countrywide Financial, as they could no longer obtain financing through the credit markets.