Deflation

[2] Economists generally believe that a sudden deflationary shock is a problem in a modern economy because it increases the real value of debt, especially if the deflation is unexpected.

[3][4][5][6][7][8][9] Some economists argue that prolonged deflationary periods are related to the underlying technological progress in an economy, because as productivity increases (TFP), the cost of goods decreases.

[15] Deflation is also related to risk aversion, where investors and buyers will start hoarding money because its value is now increasing over time.

Most nations abandoned the gold standard in the 1930s so that there is less reason to expect deflation, aside from the collapse of speculative asset classes, under a fiat monetary system with low productivity growth.

By contrast, under a fiat monetary system, there was high productivity growth from the end of World War II until the 1960s, but no deflation.

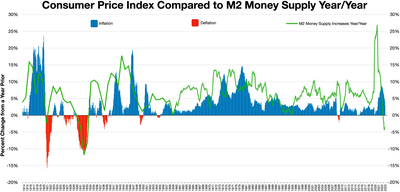

[28] In recent years changes in the money supply have historically taken a long time to show up in the price level, with a rule of thumb lag of at least 18 months.

[29][full citation needed] Bonds, equities and commodities have been suggested as reservoirs for buffering changes in the money supply.

[30] In modern credit-based economies, deflation may be caused by the central bank initiating higher interest rates (i.e., to "control" inflation), thereby possibly popping an asset bubble.

To slow or halt the deflationary spiral, banks will often withhold collecting on non-performing loans (as in Japan, and most recently America and Spain).

Episodes of deflation have been rare and brief since the Federal Reserve was created (a notable exception being the Great Depression) while U.S. economic progress has been unprecedented.

The United States had no national paper money until 1862 (greenbacks used to fund the Civil War), but these notes were discounted to gold until 1877.

[27] When structural deflation appeared in the years following 1870, a common explanation given by various government inquiry committees was a scarcity of gold and silver, although they usually mentioned the changes in industry and trade we now call productivity.

Furthermore, Wells argued that the deflation only lowered the cost of goods that benefited from recent improved methods of manufacturing and transportation.

Some believe that, in the absence of large amounts of debt, deflation would be a welcome effect because the lowering of prices increases purchasing power.

When the short-term interest rate hits zero, the central bank can no longer ease policy by lowering its usual interest-rate target.

[citation needed] Friedrich Hayek, a libertarian Austrian-school economist, wrote that: It is agreed that hoarding money, whether in cash or in idle balances, is deflationary in its effects.

With the rise of monetarist ideas, the focus in fighting deflation was put on expanding demand by lowering interest rates (i.e., reducing the "cost" of money).

This view has received criticism in light of the failure of accommodative policies in both Japan and the US to spur demand after stock market shocks in the early 1990s and in 2000–2002, respectively.

Following the Asian financial crisis in late 1997, Hong Kong experienced a long period of deflation which did not end until the fourth quarter of 2004.

The situation was worsened by the increasingly cheap exports from mainland China, and "weak consumer confidence" in Hong Kong.

This deflation was accompanied by an economic slump that was more severe and prolonged than those of the surrounding countries that devalued their currencies in the wake of the Asian financial crisis.

[46][47] In February 2009, Ireland's Central Statistics Office announced that during January 2009, the country experienced deflation, with prices falling by 0.1% from the same time in 2008.

[40] The Bank of Japan and the government tried to eliminate it by reducing interest rates and "quantitative easing," but did not create a sustained increase in broad money and deflation persisted.

[69] It was not until 2014 that new economic policies laid out by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe finally allowed for significant levels of inflation to return.

[70] However, the COVID-19 recession once again led to deflation in 2020, with consumer good prices quickly falling, prompting heavy government stimulus worth over 20% of GDP.

The motivation for this policy change was to finance World War I; one of the results was inflation, and a rise in the gold price, along with the corresponding drop in international exchange rates for the pound.

It was possibly spurred by return to a gold standard, retiring paper money printed during the Civil War: The Great Sag of 1873–96 could be near the top of the list.

It delivered a generation's worth of rising bond prices, as well as the usual losses to unwary creditors via defaults and early calls.

[79]) The fourth was in 1930–1933 when the rate of deflation was approximately 10 percent/year, part of the United States' slide into the Great Depression, where banks failed and unemployment peaked at 25%.

Economist Nouriel Roubini predicted that the United States would enter a deflationary recession, and coined the term "stag-deflation" to describe it.