Delphi

The pass is of the river Pleistos, running from east to west, forming a natural boundary across the north of the Desfina Peninsula, and providing an easy route across it.

Among the finds stands out a tiny leopard made of mother of pearl, possibly of Sassanian origin, on display in the ground floor gallery of the Delphi Archaeological Museum.

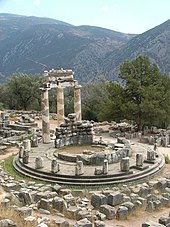

[21] From the entrance of the upper site, continuing up the slope on the Sacred Way almost to the Temple of Apollo, are a large number of votive statues, and numerous so-called treasuries.

[14] The stoa, or open-sided, covered porch, is placed in an approximately east–west alignment along the base of the polygonal wall retaining the terrace on which the Temple of Apollo sits.

[23] The koilon (cavea) leans against the natural slope of the mountain whereas its eastern part overrides a little torrent that led the water of the fountain Cassotis right underneath the temple of Apollo.

Parke asserts that there is no Apollo, no Zeus, no Hera, and certainly never was a great, serpent-like monster, and that the myths are pure Plutarchian figures of speech, meant to be aetiologies of some oracular tradition.

[38][39] According to Aeschylus in the prologue of the Eumenides, the oracle had origins in prehistoric times and the worship of Gaia, a view echoed by H. W. Parke, who described the evolution of beliefs associated with the site.

He established that the prehistoric foundation of the oracle is described by three early writers: the author of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, Aeschylus in the prologue to the Eumenides, and Euripides in a chorus in the Iphigeneia in Tauris.

Parke goes on to say, "This version [Euripides] evidently reproduces in a sophisticated form the primitive tradition which Aeschylus for his own purposes had been at pains to contradict: the belief that Apollo came to Delphi as an invader and appropriated for himself a previously existing oracle of Earth.

So much is implied by their allusions to tripods and prophetic seats... [he continues on p. 6] ...Another very archaic feature at Delphi also confirms the ancient associations of the place with the Earth goddess.

His origin has been the subject of much learned controversy: it is sufficient for our purpose to take him as the Homeric Hymn represents him – a northern intruder – and his arrival must have occurred in the dark interval between Mycenaean and Hellenic times.

[45] Another legend held that Apollo walked to Delphi from the north and stopped at Tempe, a city in Thessaly, to pick laurel (also known as bay tree) which he considered to be a sacred plant.

[55] The Delphic oracle exerted considerable influence throughout the Greek world, and she was consulted before all major undertakings including wars and the founding of colonies.

Rome's seventh and last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, after witnessing a snake near his palace, sent a delegation including two of his sons to consult the oracle.

[66] Additionally, according to Plutarch's essay on the meaning of the "E at Delphi"—the only literary source for the inscription—there was also inscribed at the temple a large letter E.[67] Among other things epsilon signifies the number 5.

[72] The spring at the site flowed toward the temple but disappeared beneath, creating a cleft which emitted chemical vapors that purportedly caused the oracle at Delphi to reveal her prophecies.

Erwin Rohde wrote that the Python was an earth spirit, who was conquered by Apollo, and buried under the omphalos, and that it is a case of one deity setting up a temple on the grave of another.

Krisa's power was broken finally by the recovered Aeolic and Attic-Ionic speaking states of southern Greece over the issue of access to Delphi.

Initially under the control of Phocian settlers based in nearby Kirra (currently Itea), Delphi was reclaimed by the Athenians during the First Sacred War (597–585 BC).

When the doctor Oreibasius visited the oracle of Delphi, in order to question the fate of paganism, he received a pessimistic answer:[citation needed] Tell the king that the flute has fallen to the ground.

Phoebus does not have a home any more, neither an oracular laurel, nor a speaking fountain, because the talking water has dried outIt was shut down during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire by Theodosius I in 381 AD.

Delphi would have been a renowned city regardless of whether it hosted these games; it had other attractions that led to it being labeled the "omphalos" (navel) of the earth, in other words, the centre of the world.

It seems that one of the first buildings of the early modern era was the monastery of the Dormition of Mary or of Panagia (the Mother of God) built above the ancient gymnasium at Delphi.

The first Westerner to describe the remains in Delphi was Cyriacus of Ancona, a fifteenth-century merchant turned diplomat and antiquarian, considered the founding father of modern classical archeology.

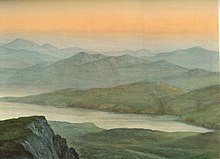

In 1766, an English expedition funded by the Society of Dilettanti included the Oxford epigraphist Richard Chandler, the architect Nicholas Revett, and the painter William Pars.

The earliest depictions of Delphi were totally imaginary; for example, those created by Nikolaus Gerbel, who published in 1545 a text based on the map of Greece by N. Sofianos.

[87] The first travelers with archaeological interests, apart from the precursor Cyriacus of Ancona, were the British George Wheler and the French Jacob Spon, who visited Greece in a joint expedition in 1675–1676.

Travelers continued to visit Delphi throughout the nineteenth century and published their books which contained diaries, sketches, and views of the site, as well as pictures of coins.

The French author relates in a charming style his adventures on the road, praising particularly the ability of an old woman to put back in place the dislocated arm of one of his foreign traveling companions, who had fallen off the horse.

The revolutionary "pocket" books invented by Karl Baedeker, accompanied by maps useful for visiting archaeological sites such as Delphi (1894) and the informed plans, the guides became practical and popular.