Hydrostatics

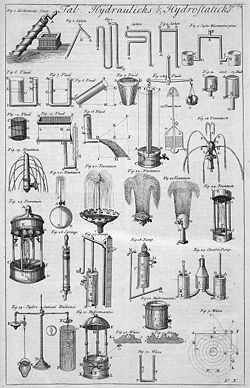

Hydrostatics is fundamental to hydraulics, the engineering of equipment for storing, transporting and using fluids.

It is also relevant to geophysics and astrophysics (for example, in understanding plate tectonics and the anomalies of the Earth's gravitational field), to meteorology, to medicine (in the context of blood pressure), and many other fields.

Hydrostatics offers physical explanations for many phenomena of everyday life, such as why atmospheric pressure changes with altitude, why wood and oil float on water, and why the surface of still water is always level according to the curvature of the earth.

Some principles of hydrostatics have been known in an empirical and intuitive sense since antiquity, by the builders of boats, cisterns, aqueducts and fountains.

Archimedes is credited with the discovery of Archimedes' Principle, which relates the buoyancy force on an object that is submerged in a fluid to the weight of fluid displaced by the object.

The Roman engineer Vitruvius warned readers about lead pipes bursting under hydrostatic pressure.

[3] The concept of pressure and the way it is transmitted by fluids was formulated by the French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal in 1647.

[citation needed] The "fair cup" or Pythagorean cup, which dates from about the 6th century BC, is a hydraulic technology whose invention is credited to the Greek mathematician and geometer Pythagoras.

[citation needed] Pascal made contributions to developments in both hydrostatics and hydrodynamics.

However, fluids can exert pressure normal to any contacting surface.

If this were not the case, the fluid would move in the direction of the resulting force.

Thus, the pressure on a fluid at rest is isotropic; i.e., it acts with equal magnitude in all directions.

where: For water and other liquids, this integral can be simplified significantly for many practical applications, based on the following two assumptions.

of the fluid column between z and z0 is often reasonably small compared to the radius of the Earth, one can neglect the variation of g. Under these circumstances, one can transport out of the integral the density and the gravity acceleration and the law is simplified into the formula where

is the height z − z0 of the liquid column between the test volume and the zero reference point of the pressure.

[4][5] One could arrive to the above formula also by considering the first particular case of the equation for a conservative body force field: in fact the body force field of uniform intensity and direction:

Then the body force density has a simple scalar potential:

is the total height of the liquid column above the test area to the surface, and p0 is the atmospheric pressure, i.e., the pressure calculated from the remaining integral over the air column from the liquid surface to infinity.

Hydrostatic pressure has been used in the preservation of foods in a process called pascalization.

This pressure forces plasma and nutrients out of the capillaries and into surrounding tissues.

[7] Statistical mechanics shows that, for a pure ideal gas of constant temperature in a gravitational field, T, its pressure, p will vary with height, h, as where This is known as the barometric formula, and may be derived from assuming the pressure is hydrostatic.

Any body of arbitrary shape which is immersed, partly or fully, in a fluid will experience the action of a net force in the opposite direction of the local pressure gradient.

[8] In the case of a ship, for instance, its weight is balanced by pressure forces from the surrounding water, allowing it to float.

[citation needed] Discovery of the principle of buoyancy is attributed to Archimedes.

The horizontal and vertical components of the hydrostatic force acting on a submerged surface are given by the following formula:[8] where Liquids can have free surfaces at which they interface with gases, or with a vacuum.

In general, the lack of the ability to sustain a shear stress entails that free surfaces rapidly adjust towards an equilibrium.

However, on small length scales, there is an important balancing force from surface tension.

When liquids are constrained in vessels whose dimensions are small, compared to the relevant length scales, surface tension effects become important leading to the formation of a meniscus through capillary action.

This capillary action has profound consequences for biological systems as it is part of one of the two driving mechanisms of the flow of water in plant xylem, the transpirational pull.

The drop's surface tension is directly proportional to the cohesion property of the fluid.