Material properties of diamond

Known to the ancient Greeks as ἀδάμας (adámas, 'proper, unalterable, unbreakable')[3] and sometimes called adamant, diamond is the hardest known naturally occurring material, and serves as the definition of 10 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness.

From theoretical considerations, lonsdaleite is expected to be harder than diamond, but the size and quality of the available stones are insufficient to test this hypothesis.

Diamonds which are nearly round, due to the formation of multiple steps on octahedral faces, are commonly coated in a gum-like skin (nyf).

A curious side effect of a natural diamond's surface perfection is hydrophobia combined with lipophilia.

Treatment with gases or plasmas containing the appropriate gas, at temperatures of 450 °C or higher, can change the surface property completely.

[10] Naturally occurring diamonds have a surface with less than a half monolayer coverage of oxygen, the balance being hydrogen and the behavior is moderately hydrophobic.

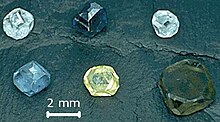

[18] Diamonds occur in various colors: black, brown, yellow, gray, white, blue, orange, purple to pink, and red.

If the nitrogen atoms are dispersed throughout the crystal in isolated sites (not paired or grouped), they give the stone an intense yellow or occasionally brown tint (type Ib); the rare canary diamonds belong to this type, which represents only ~0.1% of known natural diamonds.

Type Ia and Ib diamonds absorb in both the infrared and ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum, from 320 nm.

[19] Certain diamond enhancement techniques are commonly used to artificially produce an array of colors, including blue, green, yellow, red, and black.

These high-energy particles physically alter the diamond's crystal lattice, knocking carbon atoms out of place and producing color centers.

The depth of color penetration depends on the technique and its duration, and in some cases the diamond may be left radioactive to some degree.

Its high dispersion of 0.044 (variation of refractive index across the visible spectrum) manifests in the perceptible fire of cut diamonds.

[22] More than 20 other minerals have higher dispersion (that is difference in refractive index for blue and red light) than diamond, such as titanite 0.051, andradite 0.057, cassiterite 0.071, strontium titanate 0.109, sphalerite 0.156, synthetic rutile 0.330, cinnabar 0.4, etc.

[24] However, the combination of dispersion with extreme hardness, wear and chemical resistivity, as well as clever marketing, determines the exceptional value of diamond as a gemstone.

Diamonds exhibit fluorescence, that is, they emit light of various colors and intensities under long-wave ultraviolet light (365 nm): Cape series stones (type Ia) usually fluoresce blue, and these stones may also phosphoresce yellow, a unique property among gemstones.

Other possible long-wave fluorescence colors are green (usually in brown stones), yellow, mauve, or red (in type IIb diamonds).

[26] However, blue emission in type Ia diamond could be either due to dislocations or the N3 defects (three nitrogen atoms bordering a vacancy).

[30] Type IIb diamonds may absorb in the far red due to the substitutional boron, but otherwise show no observable visible absorption spectrum.

Most natural blue diamonds are an exception and are semiconductors due to substitutional boron impurities replacing carbon atoms.

N-type diamond films are reproducibly synthesized by phosphorus doping during chemical vapor deposition.

[37] In January 2024, a Japanese research team fabricated a MOSFET using phosphorus-doped n-type diamond, which would have superior characteristics to silicon-based technology in high-temperature, high-frequency or high-electron mobility applications.

[39] In April 2004, research published in the journal Nature reported that below 4 K, synthetic boron-doped diamond is a bulk superconductor.

[40] Superconductivity was later observed in heavily boron-doped films grown by various chemical vapor deposition techniques, and the highest reported transition temperature (by 2009) is 11.4 K.[41][42] (See also Covalent superconductor#Diamond) Uncommon magnetic properties (spin glass state) were observed in diamond nanocrystals intercalated with potassium.

[43] Unlike paramagnetic host material, magnetic susceptibility measurements of intercalated nanodiamond revealed distinct ferromagnetic behavior at 5 K. This is essentially different from results of potassium intercalation in graphite or C60 fullerene, and shows that sp3 bonding promotes magnetic ordering in carbon.

Unlike most electrical insulators, diamond is a good conductor of heat because of the strong covalent bonding and low phonon scattering.

[44][45] Because diamond has such high thermal conductance it is already used in semiconductor manufacture to prevent silicon and other semiconducting materials from overheating.

However, older probes will be fooled by moissanite, a crystalline mineral form of silicon carbide introduced in 1998 as an alternative to diamonds, which has a similar thermal conductivity.

[8][31] Technologically, the high thermal conductivity of diamond is used for the efficient heat removal in high-end power electronics.

[22] However, owing to a very large kinetic energy barrier, diamonds are metastable; they will not decay into graphite under normal conditions.