Differential interference contrast microscopy

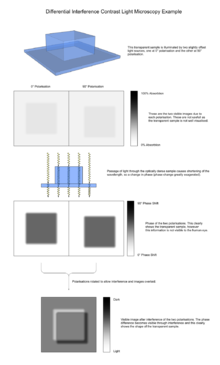

DIC works on the principle of interferometry to gain information about the optical path length of the sample, to see otherwise invisible features.

A relatively complex optical system produces an image with the object appearing black to white on a grey background.

Adding an adjustable offset phase determining the interference at zero optical path difference in the sample, the contrast is proportional to the path length gradient along the shear direction, giving the appearance of a three-dimensional physical relief corresponding to the variation of optical density of the sample, emphasising lines and edges though not providing a topographically accurate image.

This causes a change in phase of one ray relative to the other due to the delay experienced by the wave in the more optically dense material.

The image has the appearance of a three-dimensional object under very oblique illumination, causing strong light and dark shadows on the corresponding faces.

The typical phase difference giving rise to the interference is very small, very rarely being larger than 90° (a quarter of the wavelength).

When sequentially shifted images are collated, the phase-shift introduced by the object can be decoupled from unwanted non-interferometric artifacts, which typically results in an improvement in contrast, especially in turbid samples.

[3] DIC is used for imaging live and unstained biological samples, such as a smear from a tissue culture or individual water borne single-celled organisms.

However analysis of DIC images must always take into account the orientation of the Wollaston prisms and the apparent lighting direction, as features parallel to this will not be visible.