Directional derivative

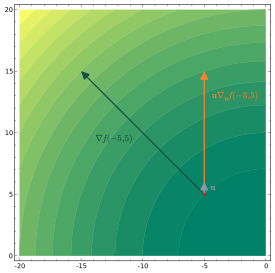

[citation needed] The directional derivative of a multivariable differentiable (scalar) function along a given vector v at a given point x intuitively represents the instantaneous rate of change of the function, moving through x with a direction specified by v. The directional derivative of a scalar function f with respect to a vector v at a point (e.g., position) x may be denoted by any of the following:

[2] If the function f is differentiable at x, then the directional derivative exists along any unit vector v at x, and one has

and using the definition of the derivative as a limit which can be calculated along this path to get:

[5] This definition gives the rate of increase of f per unit of distance moved in the direction given by v. In this case, one has

These include, for any functions f and g defined in a neighborhood of, and differentiable at, p: Let M be a differentiable manifold and p a point of M. Suppose that f is a function defined in a neighborhood of p, and differentiable at p. If v is a tangent vector to M at p, then the directional derivative of f along v, denoted variously as df(v) (see Exterior derivative),

(see Tangent space § Definition via derivations), can be defined as follows.

is given by the difference of two directional derivatives (with vanishing torsion):

It can be argued[7] that the noncommutativity of the covariant derivatives measures the curvature of the manifold:

In the Poincaré algebra, we can define an infinitesimal translation operator P as

(the i ensures that P is a self-adjoint operator) For a finite displacement λ, the unitary Hilbert space representation for translations is[8]

This is a translation operator in the sense that it acts on multivariable functions f(x) as

In standard single-variable calculus, the derivative of a smooth function f(x) is defined by (for small ε)

is the directional derivative along the infinitesimal displacement ε.

We have found the infinitesimal version of the translation operator:

It is evident that the group multiplication law[10] U(g)U(f)=U(gf) takes the form

So suppose that we take the finite displacement λ and divide it into N parts (N→∞ is implied everywhere), so that λ/N=ε.

Then by applying U(ε) N times, we can construct U(λ):

As a technical note, this procedure is only possible because the translation group forms an Abelian subgroup (Cartan subalgebra) in the Poincaré algebra.

We also note that Poincaré is a connected Lie group.

It is a group of transformations T(ξ) that are described by a continuous set of real parameters

The group multiplication law takes the form

For a small neighborhood around the identity, the power series representation

Suppose that U(T(ξ)) form a non-projective representation, i.e.,

is by definition symmetric in its indices, we have the standard Lie algebra commutator:

The generators for translations are partial derivative operators, which commute:

It may be shown geometrically that an infinitesimal right-handed rotation changes the position vector x by

The definitions of directional derivatives for various situations are given below.

It is assumed that the functions are sufficiently smooth that derivatives can be taken.

be a real valued function of the second order tensor

Media related to Directional derivative at Wikimedia Commons