Disruptive innovation

[1] The term, "disruptive innovation" was popularized by the American academic Clayton Christensen and his collaborators beginning in 1995,[2] but the concept had been previously described in Richard N. Foster's book Innovation: The Attacker's Advantage and in the paper "Strategic responses to technological threats",[3] as well as by Joseph Schumpeter in the book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (as creative destruction).

The article is aimed at both management executives who make the funding or purchasing decisions in companies, as well as the research community, which is largely responsible for introducing the disruptive vector to the consumer market.

In keeping with the insight that a persuasive advertising campaign can be just as effective as technological sophistication at bringing a successful product to market, Christensen's theory explains why many disruptive innovations are not advanced or useful technologies, rather combinations of existing off-the-shelf components, applied shrewdly to a fledgling value network.

In an interview with Forbes magazine he stated:"Uber helped me realize that it isn’t that being at the bottom of the market is the causal mechanism, but that it’s correlated with a business model that is unattractive to its competitor".

"[20] The current theoretical understanding of disruptive innovation is different from what might be expected by default, an idea that Clayton M. Christensen called the "technology mudslide hypothesis".

At that time, the established firm in that network can at best only fend off the market share attack with a me-too entry, for which survival (not thriving) is the only reward.

Generally, disruptive innovations were technologically straightforward, consisting of off-the-shelf components put together in a product architecture that was often simpler than prior approaches.

They offered a different package of attributes valued only in emerging markets remote from, and unimportant to, the mainstream.

[23] He argued that disruptive innovations can hurt successful, well-managed companies that are responsive to their customers and have excellent research and development.

While Christensen argued that disruptive innovations can hurt successful, well-managed companies, O'Ryan countered that "constructive" integration of existing, new, and forward-thinking innovation could improve the economic benefits of these same well-managed companies, once decision-making management understood the systemic benefits as a whole.

In low-end disruption, the disruptor is focused initially on serving the least profitable customer, who is happy with a good enough product.

[27] Jill Lepore points out that some companies identified by the theory as victims of disruption a decade or more ago, rather than being defunct, remain dominant in their industries today (including Seagate Technology, U.S. Steel, and Bucyrus).

[27] Lepore questions whether the theory has been oversold and misapplied, as if it were able to explain everything in every sphere of life, including not just business but education and public institutions.

In the long run, high (disruptive) technology bypasses, upgrades, or replaces the outdated support network.

A new high-technology core emerges and challenges existing technology support nets (TSNs), which are thus forced to coevolve with it.

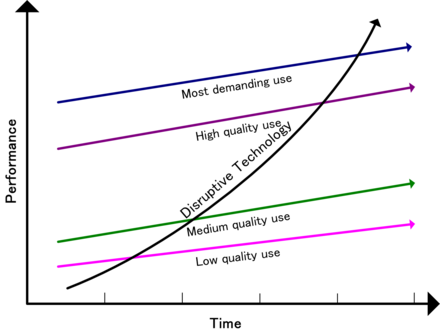

They do, however, have two important characteristics: First, they typically present a different package of performance attributes—ones that, at least at the outset, are not valued by existing customers.

Second, the performance attributes that existing customers do value improve at such a rapid rate that the new technology can later invade those established markets.

Joseph Bower[37] explained the process of how disruptive technology, through its requisite support net, dramatically transforms a certain industry.

When the technology that has the potential for revolutionizing an industry emerges, established companies typically see it as unattractive: it’s not something their mainstream customers want, and its projected profit margins aren’t sufficient to cover big-company cost structure.

Middle management resists business process reengineering because BPR represents a direct assault on the support net (coordinative hierarchy) they thrive on.

High technology therefore transforms the qualitative nature of the TSN's tasks and their relations, as well as their requisite physical, energy, and information flows.

Some information systems are still designed to improve the traditional hierarchy of command and thus preserve and entrench the existing TSN.

As knowledge surpasses capital, labor, and raw materials as the dominant economic resource, technologies are also starting to reflect this shift.

Nowadays knowledge does not reside in a super-mind, super-book, or super-database, but in a complex relational pattern of networks brought forth to coordinate human action.

[48][49] In the practical world, the popularization of personal computers illustrates how knowledge contributes to the ongoing technology innovation.

This short transitional period was necessary for getting used to the new computing environment, but was inadequate from the vantage point of producing knowledge.

Instead, Uber was launched in San Francisco, a large urban city with an established taxi service and did not target low-end customers or create a new market (from the consumer perspective).

Microsoft's Encarta, a 1993 entry into professionally edited digital encyclopedias, was once a major rival to Britannica but was discontinued in 2009.

CRT technologies did improve in the late 1990s with advances like true-flat panels and digital controls; these updates were not enough to prevent CRTs from being displaced by flat-panel LCD displays.

In the same manner, high-resolution digital video recording has replaced film stock, except for high-budget motion pictures and fine art.