Divergence theorem

Intuitively, it states that "the sum of all sources of the field in a region (with sinks regarded as negative sources) gives the net flux out of the region".

The divergence theorem is an important result for the mathematics of physics and engineering, particularly in electrostatics and fluid dynamics.

A moving liquid has a velocity—a speed and a direction—at each point, which can be represented by a vector, so that the velocity of the liquid at any moment forms a vector field.

This will cause a net outward flow through the surface S. The flux outward through S equals the volume rate of flow of fluid into S from the pipe.

If there are multiple sources and sinks of liquid inside S, the flux through the surface can be calculated by adding up the volume rate of liquid added by the sources and subtracting the rate of liquid drained off by the sinks.

The volume rate of flow of liquid through a source or sink (with the flow through a sink given a negative sign) is equal to the divergence of the velocity field at the pipe mouth, so adding up (integrating) the divergence of the liquid throughout the volume enclosed by S equals the volume rate of flux through S. This is the divergence theorem.

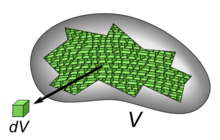

(in the case of n = 3, V represents a volume in three-dimensional space) which is compact and has a piecewise smooth boundary S (also indicated with

In terms of the intuitive description above, the left-hand side of the equation represents the total of the sources in the volume V, and the right-hand side represents the total flow across the boundary S. The divergence theorem follows from the fact that if a volume V is partitioned into separate parts, the flux out of the original volume is equal to the algebraic sum of the flux out of each component volume.

[6][7] This is true despite the fact that the new subvolumes have surfaces that were not part of the original volume's surface, because these surfaces are just partitions between two of the subvolumes and the flux through them just passes from one volume to the other and so cancels out when the flux out of the subvolumes is summed.

Therefore: Since the union of surfaces S1 and S2 is S This principle applies to a volume divided into any number of parts, as shown in the diagram.

[7] Since the integral over each internal partition (green surfaces) appears with opposite signs in the flux of the two adjacent volumes they cancel out, and the only contribution to the flux is the integral over the external surfaces (grey).

As the volume is divided into smaller and smaller parts, the surface integral on the right, the flux out of each subvolume, approaches zero because the surface area S(Vi) approaches zero.

[7] As long as the vector field F(x) has continuous derivatives, the sum above holds even in the limit when the volume is divided into infinitely small increments As

In the last equality we used the Voss-Weyl coordinate formula for the divergence, although the preceding identity could be used to define

By a variant of the straightening theorem for vector fields, we may choose

By replacing F in the divergence theorem with specific forms, other useful identities can be derived (cf.

[10] Suppose we wish to evaluate where S is the unit sphere defined by and F is the vector field The direct computation of this integral is quite difficult, but we can simplify the derivation of the result using the divergence theorem, because the divergence theorem says that the integral is equal to: where W is the unit ball: Since the function y is positive in one hemisphere of W and negative in the other, in an equal and opposite way, its total integral over W is zero.

Continuity equations offer more examples of laws with both differential and integral forms, related to each other by the divergence theorem.

In fluid dynamics, electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, relativity theory, and a number of other fields, there are continuity equations that describe the conservation of mass, momentum, energy, probability, or other quantities.

The divergence theorem states that any such continuity equation can be written in a differential form (in terms of a divergence) and an integral form (in terms of a flux).

The derivation of the Gauss's law-type equation from the inverse-square formulation or vice versa is exactly the same in both cases; see either of those articles for details.

[12] Joseph-Louis Lagrange introduced the notion of surface integrals in 1760 and again in more general terms in 1811, in the second edition of his Mécanique Analytique.

Lagrange employed surface integrals in his work on fluid mechanics.

[14] Carl Friedrich Gauss was also using surface integrals while working on the gravitational attraction of an elliptical spheroid in 1813, when he proved special cases of the divergence theorem.

[16] But it was Mikhail Ostrogradsky, who gave the first proof of the general theorem, in 1826, as part of his investigation of heat flow.

[17] Special cases were proven by George Green in 1828 in An Essay on the Application of Mathematical Analysis to the Theories of Electricity and Magnetism,[18][16] Siméon Denis Poisson in 1824 in a paper on elasticity, and Frédéric Sarrus in 1828 in his work on floating bodies.

[19][16] To verify the planar variant of the divergence theorem for a region

Thus Let's say we wanted to evaluate the flux of the following vector field defined by

One can use the generalised Stokes' theorem to equate the n-dimensional volume integral of the divergence of a vector field F over a region U to the (n − 1)-dimensional surface integral of F over the boundary of U: This equation is also known as the divergence theorem.

Writing the theorem in Einstein notation: suggestively, replacing the vector field F with a rank-n tensor field T, this can be generalized to:[20] where on each side, tensor contraction occurs for at least one index.