Drug design

[1] The drug is most commonly an organic small molecule that activates or inhibits the function of a biomolecule such as a protein, which in turn results in a therapeutic benefit to the patient.

[6] Although design techniques for prediction of binding affinity are reasonably successful, there are many other properties, such as bioavailability, metabolic half-life, and side effects, that first must be optimized before a ligand can become a safe and effictive drug.

[7] Furthermore, in vitro experiments complemented with computation methods are increasingly used in early drug discovery to select compounds with more favorable ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) and toxicological profiles.

[8] A biomolecular target (most commonly a protein or a nucleic acid) is a key molecule involved in a particular metabolic or signaling pathway that is associated with a specific disease condition or pathology or to the infectivity or survival of a microbial pathogen.

[9] In some cases, small molecules will be designed to enhance or inhibit the target function in the specific disease modifying pathway.

[14] For example, nanomedicines based on mRNA can streamline and expedite the drug development process, enabling transient and localized expression of immunostimulatory molecules.

[15] In vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA allows for delivery to various accessible cell types via the blood or alternative pathways.

The use of IVT mRNA serves to convey specific genetic information into a person's cells, with the primary objective of preventing or altering a particular disease.

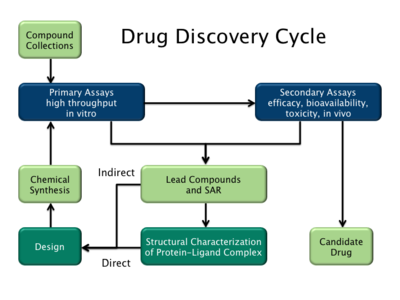

It uses the process of phenotypic screening on collections of synthetic small molecules, natural products, or extracts within chemical libraries to pinpoint substances exhibiting beneficial therapeutic effects.

Phenotypic discovery uses a practical and target-independent approach to generate initial leads, aiming to discover pharmacologically active compounds and therapeutics that operate through novel drug mechanisms.

[17] This method allows the exploration of disease phenotypes to find potential treatments for conditions with unknown, complex, or multifactorial origins, where the understanding of molecular targets is insufficient for effective intervention.

[18] Rational drug design (also called reverse pharmacology) begins with a hypothesis that modulation of a specific biological target may have therapeutic value.

The search for small molecules that bind to the target is begun by screening libraries of potential drug compounds.

Ideally, the candidate drug compounds should be "drug-like", that is they should possess properties that are predicted to lead to oral bioavailability, adequate chemical and metabolic stability, and minimal toxic effects.

[24] Finally because of the limitations in the current methods for prediction of activity, drug design is still very much reliant on serendipity[25] and bounded rationality.

These methods use linear regression, machine learning, neural nets or other statistical techniques to derive predictive binding affinity equations by fitting experimental affinities to computationally derived interaction energies between the small molecule and the target.

The reality is that present computational methods are imperfect and provide, at best, only qualitatively accurate estimates of affinity.

Computational methods have accelerated discovery by reducing the number of iterations required and have often provided novel structures.

Alternatively, a quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR), in which a correlation between calculated properties of molecules and their experimentally determined biological activity, may be derived.

In this method, ligand molecules are built up within the constraints of the binding pocket by assembling small pieces in a stepwise manner.

Selective high affinity binding to the target is generally desirable since it leads to more efficacious drugs with fewer side effects.

[45] One early general-purposed empirical scoring function to describe the binding energy of ligands to receptors was developed by Böhm.

Each component reflects a certain kind of free energy alteration during the binding process between a ligand and its target receptor.

For example, the change in polar surface area upon ligand binding can be used to estimate the desolvation energy.

Finally the interaction energy can be estimated using methods such as the change in non polar surface, statistically derived potentials of mean force, the number of hydrogen bonds formed, etc.

In practice, the components of the master equation are fit to experimental data using multiple linear regression.

This can be done with a diverse training set including many types of ligands and receptors to produce a less accurate but more general "global" model or a more restricted set of ligands and receptors to produce a more accurate but less general "local" model.

[49] A particular example of rational drug design involves the use of three-dimensional information about biomolecules obtained from such techniques as X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy.

Computer-aided drug design in particular becomes much more tractable when there is a high-resolution structure of a target protein bound to a potent ligand.

[54][55] Emerging technologies in high-throughput screening substantially enhance processing speed and decrease the required detection volume.