Dynamic equilibrium

Reactions do in fact occur, sometimes vigorously, but to such an extent that changes in composition cannot be observed.

In a new bottle of soda, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the liquid phase has a particular value.

If half of the liquid is poured out and the bottle is sealed, carbon dioxide will leave the liquid phase at an ever-decreasing rate, and the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the gas phase will increase until equilibrium is reached.

[1] This relationship is written as where K is a temperature-dependent constant, P is the partial pressure, and c is the concentration of the dissolved gas in the liquid.

The concentration of carbon dioxide in the liquid has decreased and the drink has lost some of its fizz.

Henry's law may be derived by setting the chemical potentials of carbon dioxide in the two phases to be equal to each other.

Other constants for dynamic equilibrium involving phase changes, include partition coefficient and solubility product.

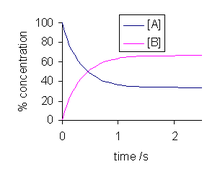

A simple example occurs with acid-base equilibrium such as the dissociation of acetic acid, in an aqueous solution.

Equilibrium is attained when the sum of chemical potentials of the species on the left-hand side of the equilibrium expression is equal to the sum of chemical potentials of the species on the right-hand side.

Dynamic equilibria can also occur in the gas phase as, for example when nitrogen dioxide dimerizes.