Dynamic mechanical analysis

Dynamic mechanical analysis (abbreviated DMA) is a technique used to study and characterize materials.

A sinusoidal stress is applied and the strain in the material is measured, allowing one to determine the complex modulus.

Polymers composed of long molecular chains have unique viscoelastic properties, which combine the characteristics of elastic solids and Newtonian fluids.

The classical theory of hydrodynamics describes the properties of viscous fluid, for which stress response depends on strain rate.

[3] The viscoelastic property of a polymer is studied by dynamic mechanical analysis where a sinusoidal force (stress σ) is applied to a material and the resulting displacement (strain) is measured.

For a purely viscous fluid, there will be a 90 degree phase lag of strain with respect to stress.

An example of such changes can be seen by blending ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) with styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) and different cross-linking or curing systems.

[6] Increasing the amount of SBR in the blend decreased the storage modulus due to intermolecular and intramolecular interactions that can alter the physical state of the polymer.

Within the glassy region, EPDM shows the highest storage modulus due to stronger intermolecular interactions (SBR has more steric hindrance that makes it less crystalline).

In the rubbery region, SBR shows the highest storage modulus resulting from its ability to resist intermolecular slippage.

[6] When compared to sulfur, the higher storage modulus occurred for blends cured with dicumyl peroxide (DCP) because of the relative strengths of C-C and C-S bonds.

Incorporation of reinforcing fillers into the polymer blends also increases the storage modulus at an expense of limiting the loss tangent peak height.

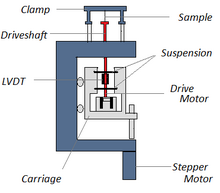

[6] The instrumentation of a DMA consists of a displacement sensor such as a linear variable differential transformer, which measures a change in voltage as a result of the instrument probe moving through a magnetic core, a temperature control system or furnace, a drive motor (a linear motor for probe loading which provides load for the applied force), a drive shaft support and guidance system to act as a guide for the force from the motor to the sample, and sample clamps in order to hold the sample being tested.

These types of analyzers force the sample to oscillate at a certain frequency and are reliable for performing a temperature sweep.

In strain control, the probe is displaced and the resulting stress of the sample is measured by implementing a force balance transducer, which utilizes different shafts.

The advantages of strain control include a better short time response for materials of low viscosity and experiments of stress relaxation are done with relative ease.

In stress control, a set force is applied to the sample and several other experimental conditions (temperature, frequency, or time) can be varied.

Characterizing low viscous materials come at a disadvantage of short time responses that are limited by inertia.

Stress and strain control analyzers give about the same results as long as characterization is within the linear region of the polymer in question.

However, stress control lends a more realistic response because polymers have a tendency to resist a load.

Torsional analyzers are mainly used for liquids or melts but can also be implemented for some solid samples since the force is applied in a twisting motion.

The instrument can do thermomechanical analysis (TMA) studies in addition to the experiments that torsional analyzers can do.

In order to utilize DMA to characterize materials, the fact that small dimensional changes can also lead to large inaccuracies in certain tests needs to be addressed.

Inertia and shear heating can affect the results of either forced or free resonance analyzers, especially in fluid samples.

A common test method involves measuring the complex modulus at low constant frequency while varying the sample temperature.

Secondary transitions can also be observed, which can be attributed to the temperature-dependent activation of a wide variety of chain motions.

and in E’’ with respect to frequency can be associated with the glass transition, which corresponds to the ability of chains to move past each other.

This sort of study provides a rich characterization of the material, and can lend information about the nature of the molecular motion responsible for the transition.

For instance, studies of polystyrene (Tg ≈110 °C) have noted a secondary transition near room temperature.

Temperature-frequency studies showed that the transition temperature is largely frequency-independent, suggesting that this transition results from a motion of a small number of atoms; it has been suggested that this is the result of the rotation of the phenyl group around the main chain.