Ecological speciation

Ecologically-driven reproductive isolation under divergent natural selection leads to the formation of new species.

This has been documented in many cases in nature and has been a major focus of research on speciation for the past few decades.

[2] However, there are numerous examples of closely related, ecologically similar species (e.g., Albinaria land snails on islands in the Mediterranean,[7] Batrachoseps salamanders from California,[8] and certain crickets[9] and damselflies[10]), which is a pattern consistent with the possibility of nonecological speciation.

The causes are outlined in the following list:[12][13][4] Populations of a species can become spatially isolated due to preferences for separate habitats.

[4] The separation decreases the chance of mating to occur between the two populations, inhibiting gene flow, and promoting pre-zygotic isolation to lead to complete speciation.

)[1]: 182–3 Identification of both forms of habitat isolation in nature is difficult due to the effects of geography.

Alternative explanations could account for the patterns:[1]: 185 These issues (with both micro- and macro-spatial isolation) can be overcome by field or laboratory experiments such as transplantation of individuals into opposite habitats[1]: 185 (though this can prove difficult if individuals are not completely unfit for the imposed habitat).

Ecological speciation caused by habitat isolation can occur in any geographic sense, that is, either allopatrically, parapatrically, or sympatrically.

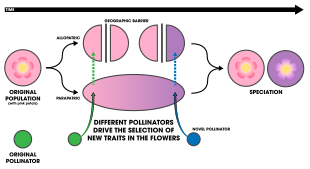

[1]: 189 A classic example of habitat isolation occurring in allopatry is that of host-specific cospeciation[1]: 189 such as in the pocket gophers and their host chewing lice[24] or in the fig wasp-fig tree relationship and the yucca-yucca moth relationship—examples of ecological speciation caused by pollinator isolation.

[1]: 191 Habitat isolation is a significant impediment to gene flow and is exhibited by the common observation that plants and animals are often spatially separated in relation to their adaptations.

When species are transplanted to alternate habitats, their viability is reduced, indicating that gene flow between the populations is unlikely.

vaseyana in Utah, where hybrid zones exists between altitudinal populations, and transplant experiments reduce the fitness of the subspecies.

[33] Ecological speciation due to sexual isolation results from differing environmental conditions that modify communication systems or mate choice patterns over time.

[4] The coastal snail species Littorina saxatilis has been a focus of research[4] as two ecotypes residing at different shore levels exhibit reproductive isolation as a result of mate choice regarding the body size differences of the ecotype.

[35][36][37][38] Evidence is also found in Neochlamisus bebbianae leaf beetles,[32] Timema cristinae walking-stick insects,[39][40] and in the butterfly species Heliconius melpomene and H. cydno which are thought to have diverged recently due to assortive mating being enhanced where the species populations meet in sympatry.

[44] For example, in the bee Eulaema cingulata, pollen from Catasetum discolor and C. saccatum is attached to different parts of the body (ventrally and dorsally respectively).

[4] E. lewisii has changed significantly from its sister species in that its evolved pink flowers, broad petals, shorter stamens (the pollen-producing part of the plant), and a lower volume of nectar.

E. cardinalis is pollinated by hummingbirds and exhibits red, tube-shaped flowers, larger stamens, and a lot of nectar.

It is thought that nectar volume as well as a genetic component (an allele substitution that controls color variation) maintains isolation.

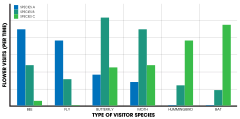

Flower size of Raphanus sativus (in this case, wild radish in 32 California populations) has been found to differ in accordance with larger honeybee pollinators.

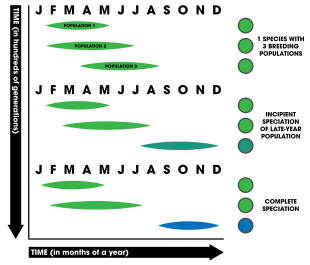

[55] A similar pattern involving the timing in which hawkmoths (Hyles lineata) are active is documented in three subspecies of Aquilegia coerulea, the Rocky Mountain columbine found across the western United States.

Unlike the inland, grassland habitat of subspecies hallackii, ocellatum resides in coastal populations and has short spurs that correlate with its primary carpenter bee pollinator.

[58] Temporal isolation is based on the reduction of gene flow between two populations due to different breeding times (phenology).

[62] The table list below summarizes a number of studies considered to be strong or compelling examples of allochronic speciation occurring in nature.

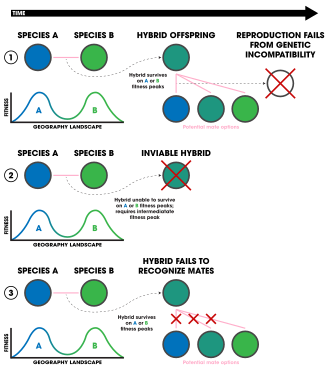

This type of speciation involves the low survival rates of migrants between populations because of their lack of adaptations to non-native habitats.

[1]: 232 Some studies involving gametic isolation in Drosophila fruit flies,[93] ground crickets,[94] and Helianthus plants[95] suggest that there may be a role in ecology; however it is undetermined.

Some studies indicate that these incompatibilities are a cause of ecological speciation because they can evolve quickly through divergent selection.

This has been detected in populations of sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus),[97][98] water-lily beetles (Galerucella nymphaeae),[99] pea aphids,[100] and tephritid flies (Eurosta solidaginis).

The end result is that the genes of each parental population are unable to intermix as they are carried by a hybrid who is unlikely to reproduce.

[102] Similar patterns have been found in lacewings[103] migrating patterns of Sylvia atricapilla bird populations,[104] wolf spiders (Schizocosa ocreata and S. rovneri) and their courtship behaviors,[105] sympatric benthic and limnetic sticklebacks (the Gasterosteus aculeatus complex),[106] and the Panamanian butterflies Anartia fatima and A.

Experiment 1: a speciation event predicted to have occurred due to an ecologically-based divergent factor giving rise to two new species (1a). The experiment produces viable and fertile hybrid offspring and places them in isolated settings that match their parental environments (1b). The experiment predicts that, "reproductive isolation should then evolve in correlation with environment, building [increasing] between populations in different environments and being absent between laboratory and natural populations from similar environments." [ 4 ]

Experiment 2: a peripatric speciation event between a mainland species and an isolated endemic population occurs (2a). A laboratory setting replicates the mainland environmental conditions thought to have driven speciation and a mainland population is placed within it. The experiment predicts that the transplant will show evidence of isolation that matches that of the island endemic (2b). [ 4 ]

1. Ecologically-independent post-zygotic isolation.

2. Ecologically-dependent post-zygotic isolation.

3. Selection against hybrids.