Economic history of Canada

Scholars of Canadian economic history were heirs to the traditions that developed in Europe and the United States, but frameworks of study that worked well elsewhere often failed in Canada.

They argued that the Canadian Economy (beyond the level of subsistence farming) was primarily based on exports of a series of staples—fish, fur, timber, wheat—that shipped to Britain and the British Empire.

Innis argued that Canada developed as it did because of the nature of its staple commodities: raw materials, such as fish, fur, lumber, agricultural products and minerals.

Innis, Influenced by the American historian Frederick Jackson Turner added a sociological dimension: different staples led to the emergence of regional economies (and societies) within Canada.

This fur trade was controlled by large firms, such as the Hudson's Bay Company and thus produced the much more centralized, business-oriented society that today characterizes Montreal and Toronto.

This trade closely involved the Native peoples who would hunt the beavers and other animals and then sell their pelts to Europeans in exchange for guns, textiles, and luxury items like mirrors and beads.

Those who traded with the Native were the voyageurs, woodsmen who travelled the length of North America to bring pelts to the ports of Montreal and Quebec City.

Unlike the United States where agriculture had become the primary industry, requiring a large labour force the population of what would be Canada remained very low.

The continued dependence on trade with Europe, also meant that the northern colonies were far more reluctant to join the American Revolution, and Canada thus remained loyal to the British crown.

The Napoleonic Wars and the Continental blockade cut off, or at least reduced the Baltic trade so the British looked northwards to the colonies that had remained loyal and were still available.

This area also proved insufficient and the trade expanded westward, most notably to the Ottawa River system, which, by 1845, provided three-quarters of the timber shipped from Quebec City.

During the early nineteenth century, with the preferential tariff in full effect, the timber ships were among the oldest and most dilapidated in the British merchant fleet, and travelling as a passenger upon them was extremely unpleasant and dangerous.

Since timber exports would peak at the same time as conflicts in Europe, such as the Napoleonic Wars, a great mass of refugees sought this cheap passage across the Atlantic.

The repeal of the Corn Laws by the Parliament of Britain in 1846, terminated colonial trading preferences and marked the symbolic end of mercantilism in Canada while ushering in the new era of capitalism.

More concerted activity was discouraged in large part by the military which posted soldiers along the line of the canal to suppress dissent and ensure a cheap supply of labour.

Leonard Tilley, New Brunswick's most ardent railway promoter, championed the cause of "economic progress", stressing that Atlantic Canadians needed to pursue the most cost-effective transportation connections possible if they wanted to expand their influence beyond local markets.

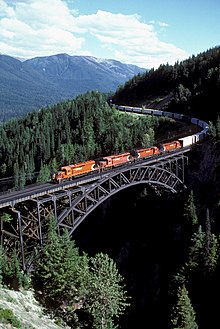

Thus metropolitan rivalries between Montreal, Halifax, and Saint John led Canada to build more railway lines per capita than any other industrializing nation, even though it lacked capital resources, and had too little freight and passenger traffic to allow the systems to turn a profit.

Den Otter (1997) challenges popular assumptions that Canada built transcontinental railways because it feared the annexationist schemes of aggressive Americans.

These economic links promoted trade, commerce, and the flow of ideas between the two countries, integrating Canada into a North American economy and culture by 1880.

[24] In the years after Confederation, the once-buoyant BNA economy soured, an event some blamed on union or government railway policy, but was more likely caused by the Long Depression that was affecting the entire world.

In the thirty years after Confederation, Canada experienced a net out flow of migrants, as a large number of Canadians relocated to the United States.

The major changes involved "mechanization of technology and a shift toward output of high-grade consumer oriented products", such as milk, eggs and vegetables for the fast-growing urban markets.

[30] Wheat was the golden crop that built the economy of the Prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta and filled outbound trains headed for ports to carry the grain to Europe.

[32] Norrie argues that the necessity of using dry farming techniques created special risks and the farmers responded by using summer fallow rather than the risky but more productive use of substitute crops or the planting of wheat every year.

Between 1908 and 1913 British firms lent vast sums to Canadian farmers to plant their wheat crops; only when the drought began in 1916 did it become clear that far too much credit had been extended.

In the 1920s, there was an unprecedented increase in the standard of living as items that had been luxury goods such as radios, automobiles, and electric lights—not to mention flush toilets—became common place across the nation.

When the American economy began to collapse in the late 1920s the close economic links and the central banking system meant that the malaise quickly spread across the border.

Population growth contracted markedly as immigration slowed, and birth rates fell as people postponed marriage and family life until they were more secure.

[46] The recession brought on in the United States by the collapse of the dot-com bubble beginning in 2000, hurt the Toronto Stock Exchange but has affected Canada only mildly.

[50] As of 2015[update], the Canadian economy has largely stabilized and has seen a modest return to growth, although the country remains troubled by volatile oil prices, sensitivity to the Eurozone crisis and higher-than-normal unemployment rates.