Effect of taxes and subsidies on price

Taxes and subsidies change the price of goods and, as a result, the quantity consumed.

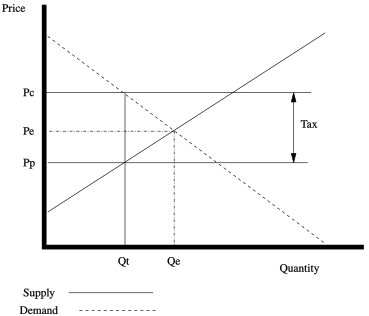

Source:[1] The effect of a specific tax levied on sellers can be divided into three steps.

This means that the business is less profitable for a given price level and the supply curve shifts upwards.

Therefore the distance between the original and the new shifted supply curve is equal to the amount of tax imposed.

In order for them to supply a given quantity of the good, the market price needs to be higher by the amount of tax to preserve net income from sales.

Last, after the shift of the supply curve is taken into account, the difference between the initial and after-tax equilibrium can be observed.

In the case of demand being more elastic than supply, the incidence of the tax falls more heavily on sellers and the consumers feel a smaller growth of price and vice versa.

If we say that the consumers pay $3.30 and the new equilibrium quantity is 80, then the producers keep $2.80 and the total tax revenue equals $0.50 x 80 = $40.00.

Similarly, a marginal subsidy on consumption will shift the demand curve to the right; when other things remain equal, this will decrease the price paid by consumers and increase the price received by producers by the same amount as if the subsidy had been granted to producers.

[2] Depending on the price elasticities of demand and supply, who bears more of the tax or who receives more of the subsidy may differ.

Where the supply curve is less elastic than the demand curve, producers bear more of the tax and receive more of the subsidy than consumers as the difference between the price producers receive and the initial market price is greater than the difference borne by consumers.

Where the demand curve is more inelastic than the supply curve, the consumers bear more of the tax and receive more of the subsidy as the difference between the price consumers pay and the initial market price is greater than the difference borne by producers.