Effects of the 1919 Florida Keys hurricane in Texas

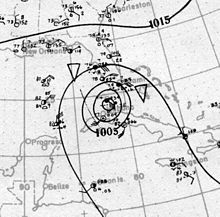

The storm originated from the Leeward Islands early in September 1919 and took a generally west-northwestward course, devastating the Florida Keys en route to the Gulf of Mexico.

Brochures from the Texas Mexican Railway described Corpus Christi as "the only coast city of the Gulf of Mexico, between Veracruz and Florida, that is absolutely secure against inundation."

U.S. Representative John Nance Garner brought forth a proposal to the Army Corps of Engineers to survey and dredge a channel from Aransas Pass to Corpus Christi's wharves.

However, the high costs involved and political divisions prevented the project from proceeding promptly; by August 1919, only property valuation of lands near the proposed seawall had been conducted.

[4][6] It struck the Dry Tortugas of Florida on September 10 with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h), ranking it as a Category 4 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale.

[8] With the storm bearing down on South Florida, Major Allen Buell of the Weather Bureau predicted that San Antonio, Texas, would not experience any inclement effects.

[10][12][13] Acknowledging that knowledge of the storm's location was "conjectural",[11]: 667 the Weather Bureau transmitted the following message to telegraph offices along the coast: Regret that no radio reports were received from Gulf of Mexico during the entire day.

Increasing northeast winds at mouth of Mississippi River indicate that storm is not far to southward of that locality, and we can only repeat previous messages urging great caution until further advices [on the morning of September 13].

Good night.Despite showers reaching the Texas Coastal Bend on September 12, Corpus Christi officials ordered the lowering of storm warning flags along the city's beaches and wharves the following day.

With the storm appearing to have passed harmlessly, residents were outdoors enjoying the cool northerly winds afforded by the nearby hurricane.

[10] However, on September 13 the northerly winds in Corpus Christi became increasingly violent and coastal swells became indicative of an approaching storm surge.

[6] Observations taken along the Texas coast on the afternoon of September 13 documented a gradual decrease in air pressure, with Galveston also reporting an increase in ocean swells.

[11]: 668 The Houston Weather Bureau office relayed a message to Corpus Christi locating the storm south of Galveston, Texas, and urging the Corpus Christi Weather Bureau to monitor the air pressure and to "take all possible precautions against rising winds and higher tides" if the pressure were to fall.

[10][6] The hurricane made landfall 25 mi (40 km) south of Corpus Christi that afternoon with sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and an air pressure of 950 mbar (hPa; 28.05 inHg).

[18] Galveston residents concurrently took refuge at hotels in Houston, with interurban service allotting additional cars hourly to facilitate their evacuation.

Rainfall totals of at least 3 in (76 mm) spanned westward towards the Pecos River valley into Hudspeth County and northward into the Texas Panhandle towards the Oklahoma border.

[11]: 669 Rough surf destroyed the East End Fishing Pier and damaged a concrete embankment at 35th Street and Seawall Boulevard.

Nearly all of the 284 verified fatalities were residents of Corpus Christi; 57 bodies were recovered in the city proper while 121 were found at nearby White Point, the highest death toll of any locality from the hurricane.

[11]: 670 The Houston Post reported a "conservative estimate" of $20 million for the total monetary loss from Corpus Christi, approximated by "prominent business men and other trained observers".

[10][20] Winds ranging between 70–110 mph (110–180 km/h) buffeted the city for roughly 17 hours between September 14–15, accompanied by a 16-foot (4.9 m) storm surge—the highest on record in Corpus Christi's history.

Beyond the immediate waterfront, the Houston Post reported that "every commercial establishment's first floor was wrecked, and in some cases the entire building rendered useless, over a corresponding area two blocks wide.

[20] Farther inland, 40–50 mph (64–80 km/h) westerly winds raked the lower Rio Grande Valley, damaging a few buildings.

The severity of the flood was unprecedented for the Rio Grande, with the Monthly Weather Review reporting that the river expanded to a width of 40–50 mi (64–80 km).

In San Antonio, the air pressure bottomed out at 998 mbar (hPa; 29.48 inHg) and winds reached 34 mph (55 km/h).

[21] Red Cross workers, military troops, and nurses arrived in Corpus Christi within six hours of the storm's passage, traveling upon relief trains running along the few tracks that withstood the hurricane.

[2] The camaraderie in the hurricane's aftermath between Boone and Miller, once political rivals, led to a resumption of the city's push to build a deep-water port.

A special meeting was convened two weeks after the storm between Boone, Miller, and U.S. Representative Carlos Bee, putting forth proposals for a deep freshwater harbor and 3-mile-long (5 km) seawall.

[21] On the seventh anniversary of the 1919 hurricane, a large party was held in celebration of the newly built deep-water port, with politicians and the press from across the country in attendance.

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown