Cell membrane

The choice of the dielectric constant used in these studies was called into question but future tests could not disprove the results of the initial experiment.

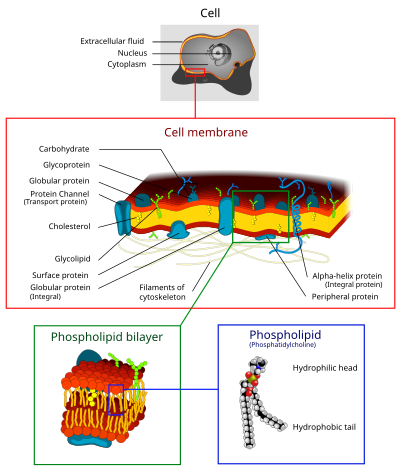

[9] Although the fluid mosaic model has been modernized to detail contemporary discoveries, the basics have remained constant: the membrane is a lipid bilayer composed of hydrophilic exterior heads and a hydrophobic interior where proteins can interact with hydrophilic heads through polar interactions, but proteins that span the bilayer fully or partially have hydrophobic amino acids that interact with the non-polar lipid interior.

The fluid mosaic model not only provided an accurate representation of membrane mechanics, it enhanced the study of hydrophobic forces, which would later develop into an essential descriptive limitation to describe biological macromolecules.

[19][20][21] Cell membranes contain a variety of biological molecules, notably lipids and proteins.

The amount of each depends upon the type of cell, but in the majority of cases phospholipids are the most abundant, often contributing for over 50% of all lipids in plasma membranes.

The fatty chains in phospholipids and glycolipids usually contain an even number of carbon atoms, typically between 16 and 20.

The length and the degree of unsaturation of fatty acid chains have a profound effect on membrane fluidity as unsaturated lipids create a kink, preventing the fatty acids from packing together as tightly, thus decreasing the melting temperature (increasing the fluidity) of the membrane.

[23][24] The ability of some organisms to regulate the fluidity of their cell membranes by altering lipid composition is called homeoviscous adaptation.

The entire membrane is held together via non-covalent interaction of hydrophobic tails, however the structure is quite fluid and not fixed rigidly in place.

Under physiological conditions phospholipid molecules in the cell membrane are in the liquid crystalline state.

[23] However, the exchange of phospholipid molecules between intracellular and extracellular leaflets of the bilayer is a very slow process.

Measuring the rate of efflux from the inside of the vesicle to the ambient solution allows researchers to better understand membrane permeability.

[citation needed] These provide researchers with a tool to examine various membrane protein functions.

Plasma membranes also contain carbohydrates, predominantly glycoproteins, but with some glycolipids (cerebrosides and gangliosides).

Recent data suggest the glycocalyx participates in cell adhesion, lymphocyte homing,[26] and many others.

Approximately a third of the genes in yeast code specifically for them, and this number is even higher in multicellular organisms.

Examples of integral proteins include ion channels, proton pumps, and g-protein coupled receptors.

[4] A G-protein coupled receptor is a single polypeptide chain that crosses the lipid bilayer seven times responding to signal molecules (i.e. hormones and neurotransmitters).

[34] Bacteria are also surrounded by a cell wall composed of peptidoglycan (amino acids and sugars).

The outer membrane of gram negative bacteria is rich in lipopolysaccharides, which are combined poly- or oligosaccharide and carbohydrate lipid regions that stimulate the cell's natural immunity.

[37] Many gram-negative bacteria have cell membranes which contain ATP-driven protein exporting systems.

Singer and G. L. Nicolson (1972), which replaced the earlier model of Davson and Danielli, biological membranes can be considered as a two-dimensional liquid in which lipid and protein molecules diffuse more or less easily.

Examples of such structures are protein-protein complexes, pickets and fences formed by the actin-based cytoskeleton, and potentially lipid rafts.

The cell membrane consists primarily of a thin layer of amphipathic phospholipids that spontaneously arrange so that the hydrophobic "tail" regions are isolated from the surrounding water while the hydrophilic "head" regions interact with the intracellular (cytosolic) and extracellular faces of the resulting bilayer.

The arrangement of hydrophilic heads and hydrophobic tails of the lipid bilayer prevent polar solutes (ex.

This affords the cell the ability to control the movement of these substances via transmembrane protein complexes such as pores, channels and gates.

Flippases and scramblases concentrate phosphatidyl serine, which carries a negative charge, on the inner membrane.

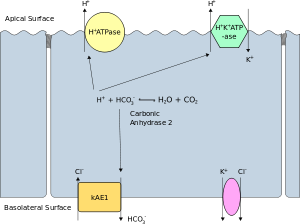

In addition, membranes in prokaryotes and in the mitochondria and chloroplasts of eukaryotes facilitate the synthesis of ATP through chemiosmosis.

Proteins (such as ion channels and pumps) are free to move from the basal to the lateral surface of the cell or vice versa in accordance with the fluid mosaic model.

The inability of charged molecules to pass through the cell membrane results in pH partition of substances throughout the fluid compartments of the body[citation needed].