Electric organ (fish)

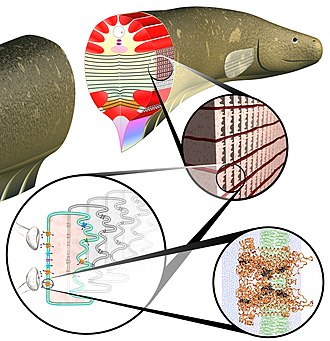

Electric organs are derived from modified muscle or in some cases nerve tissue, called electrocytes, and have evolved at least six times among the elasmobranchs and teleosts.

[9][10] Since the 20th century, electric organs have received extensive study, for example, in Hans Lissmann's pioneering 1951 paper on Gymnarchus[11] and his review of their function and evolution in 1958.

[14] However, in two marine groups, the stargazers and the torpedo rays, the electric organs are oriented along the dorso-ventral (up-down) axis.

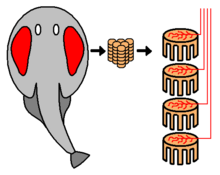

[13] The stack of electrocytes has long been compared to a voltaic pile, and may even have inspired the 1800 invention of the battery, since the analogy was already noted by Alessandro Volta.

[18][19][20][21] Notably, they have convergently evolved in the African Mormyridae and South American Gymnotidae groups of electric fish.

A whole-genome duplication event in the teleost lineage allowed for the neofunctionalization of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene Scn4aa which produces electric discharges.

[24] Comparative transcriptomics of the Mormyroidea, Siluriformes, and Gymnotiformes lineages conducted by Liu (2019) concluded that although there is no parallel evolution of entire transcriptomes of electric organs, there are a significant number of genes that exhibit parallel gene expression changes from muscle function to electric organ function at the level of pathways.

Electric organ discharges (EODs) need to vary with time for electrolocation, whether with pulses, as in the Mormyridae, or with waves, as in the Torpediniformes and Gymnarchus, the African knifefish.

[33] In the book, women develop the ability to release electrical jolts from their fingers, powerful enough to stun or kill.