Electrical resistivity and conductivity

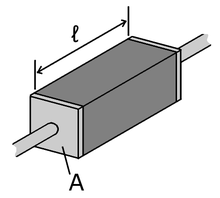

In an ideal case, cross-section and physical composition of the examined material are uniform across the sample, and the electric field and current density are both parallel and constant everywhere.

This expression simplifies to the formula given above under "ideal case" when the resistivity is constant in the material and the geometry has a uniform cross-section.

Then the electric field and current density are constant and parallel, and by the general definition of resistivity, we obtain

where the conductivity σ and resistivity ρ are rank-2 tensors, and electric field E and current density J are vectors.

Since the choice of the coordinate system is free, the usual convention is to simplify the expression by choosing an x-axis parallel to the current direction, so Jy = Jz = 0.

The actual drift velocity of electrons is typically small, on the order of magnitude of metres per hour.

However, due to the sheer number of moving electrons, even a slow drift velocity results in a large current density.

[12][13] The small decrease in conductivity on melting of pure metals is due to the loss of long range crystalline order.

[15] A consequence of this is that an electric current flowing in a loop of superconducting wire can persist indefinitely with no power source.

This is due to the motion of magnetic vortices in the electronic superfluid, which dissipates some of the energy carried by the current.

The resistance due to this effect is tiny compared with that of non-superconducting materials, but must be taken into account in sensitive experiments.

In the special case that double layers are formed, the charge separation can extend some tens of Debye lengths.

The magnitude of the potentials and electric fields must be determined by means other than simply finding the net charge density.

This can and does cause extremely complex behavior, such as the generation of plasma double layers, an object that separates charge over a few tens of Debye lengths.

The dynamics of plasmas interacting with external and self-generated magnetic fields are studied in the academic discipline of magnetohydrodynamics.

A rough summary is as follows: This table shows the resistivity (ρ), conductivity and temperature coefficient of various materials at 20 °C (68 °F; 293 K).

George Gamow tidily summed up the nature of the metals' dealings with electrons in his popular science book One, Two, Three...Infinity (1947):

The metallic substances differ from all other materials by the fact that the outer shells of their atoms are bound rather loosely, and often let one of their electrons go free.

Thus the interior of a metal is filled up with a large number of unattached electrons that travel aimlessly around like a crowd of displaced persons.

[46] In any case, a sufficiently high voltage – such as that in lightning strikes or some high-tension power lines – can lead to insulation breakdown and electrocution risk even with apparently dry wood.

n is an integer that depends upon the nature of interaction: The Bloch–Grüneisen formula is an approximation obtained assuming that the studied metal has spherical Fermi surface inscribed within the first Brillouin zone and a Debye phonon spectrum.

An investigation of the low-temperature resistivity of metals was the motivation to Heike Kamerlingh Onnes's experiments that led in 1911 to discovery of superconductivity.

The Wiedemann–Franz law states that for materials where heat and charge transport is dominated by electrons, the ratio of thermal to electrical conductivity is proportional to the temperature:

The electric resistance of a typical intrinsic (non doped) semiconductor decreases exponentially with temperature following an Arrhenius model:

As temperature increases starting from absolute zero they first decrease steeply in resistance as the carriers leave the donors or acceptors.

For example, for long-distance overhead power lines, aluminium is frequently used rather than copper (Cu) because it is lighter for the same conductance.

Silver, although it is the least resistive metal known, has a high density and performs similarly to copper by this measure, but is much more expensive.

Calcium and the alkali metals have the best resistivity-density products, but are rarely used for conductors due to their high reactivity with water and oxygen (and lack of physical strength).

In a 1774 letter to Dutch-born British scientist Jan Ingenhousz, Benjamin Franklin relates an experiment by another British scientist, John Walsh, that purportedly showed this astonishing fact: Although rarified air conducts electricity better than common air, a vacuum does not conduct electricity at all.

But having made a perfect Vacuum by means of boil’d Mercury in a long Torricellian bent Tube, its Ends immers’d in Cups full of Mercury, he finds that the Vacuum will not conduct at all, but resists the Passage of the Electric Fluid absolutely.However, to this statement a note (based on modern knowledge) was added by the editors—at the American Philosophical Society and Yale University—of the webpage hosting the letter:[63] We can only assume that something was wrong with Walsh’s findings.