Superconductivity

It is characterized by the Meissner effect, the complete cancelation of the magnetic field in the interior of the superconductor during its transitions into the superconducting state.

The occurrence of the Meissner effect indicates that superconductivity cannot be understood simply as the idealization of perfect conductivity in classical physics.

[7] It was shortly found (by Ching-Wu Chu) that replacing the lanthanum with yttrium, i.e. making YBCO, raised the critical temperature to 92 K (−181 °C), which was important because liquid nitrogen could then be used as a refrigerant.

Superconductivity was discovered on April 8, 1911, by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, who was studying the resistance of solid mercury at cryogenic temperatures using the recently produced liquid helium as a refrigerant.

[11] In 1935, Fritz and Heinz London showed that the Meissner effect was a consequence of the minimization of the electromagnetic free energy carried by superconducting current.

It was put forward by the brothers Fritz and Heinz London in 1935, shortly after the discovery that magnetic fields are expelled from superconductors.

A major triumph of the equations of this theory is their ability to explain the Meissner effect,[11] wherein a material exponentially expels all internal magnetic fields as it crosses the superconducting threshold.

Also in 1950, Maxwell and Reynolds et al. found that the critical temperature of a superconductor depends on the isotopic mass of the constituent element.

[20][21] Generalizations of BCS theory for conventional superconductors form the basis for the understanding of the phenomenon of superfluidity, because they fall into the lambda transition universality class.

[22] Two superconductors with greatly different values of the critical magnetic field are combined to produce a fast, simple switch for computer elements.

Although niobium–titanium boasts less-impressive superconducting properties than those of niobium–tin, niobium–titanium has, nevertheless, become the most widely used "workhorse" supermagnet material, in large measure a consequence of its very high ductility and ease of fabrication.

In 1962, Josephson made the important theoretical prediction that a supercurrent can flow between two pieces of superconductor separated by a thin layer of insulator.

[37] A superconductor is generally considered high-temperature if it reaches a superconducting state above a temperature of 30 K (−243.15 °C);[38] as in the initial discovery by Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller.

The Meissner effect, the quantization of the magnetic flux or permanent currents, i.e. the state of zero resistance are the most important examples.

The existence of these "universal" properties is rooted in the nature of the broken symmetry of the superconductor and the emergence of off-diagonal long range order.

Superconductors are also able to maintain a current with no applied voltage whatsoever, a property exploited in superconducting electromagnets such as those found in MRI machines.

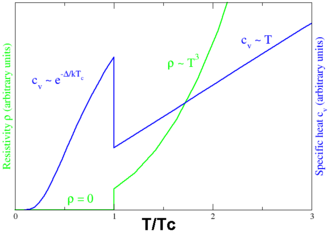

In a normal conductor, an electric current may be visualized as a fluid of electrons moving across a heavy ionic lattice.

However, as the temperature decreases far enough below the nominal superconducting transition, these vortices can become frozen into a disordered but stationary phase known as a "vortex glass".

When the material is cooled below the critical temperature, we would observe the abrupt expulsion of the internal magnetic field, which we would not expect based on Lenz's law.

The Meissner effect was given a phenomenological explanation by the brothers Fritz and Heinz London, who showed that the electromagnetic free energy in a superconductor is minimized provided

In Type I superconductors, superconductivity is abruptly destroyed when the strength of the applied field rises above a critical value Hc.

In Type II superconductors, raising the applied field past a critical value Hc1 leads to a mixed state (also known as the vortex state) in which an increasing amount of magnetic flux penetrates the material, but there remains no resistance to the flow of electric current as long as the current is not too large.

[53][54] Many other cuprate superconductors have since been discovered, and the theory of superconductivity in these materials is one of the major outstanding challenges of theoretical condensed matter physics.

[69][68] In 2018, a research team from the Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, discovered superconductivity in bilayer graphene with one layer twisted at an angle of approximately 1.1 degrees with cooling and applying a small electric charge.

Even if the experiments were not carried out in a high-temperature environment, the results are correlated less to classical but high temperature superconductors, given that no foreign atoms need to be introduced.

[71] In 2020, a room-temperature superconductor (critical temperature 288 K) made from hydrogen, carbon and sulfur under pressures of around 270 gigapascals was described in a paper in Nature.

[75] Superconductors are promising candidate materials for devising fundamental circuit elements of electronic, spintronic, and quantum technologies.

They can also be used in large wind turbines to overcome the restrictions imposed by high electrical currents, with an industrial grade 3.6 megawatt superconducting windmill generator having been tested successfully in Denmark.

The large resistance change at the transition from the normal to the superconducting state is used to build thermometers in cryogenic micro-calorimeter photon detectors.

[80] Other early markets are arising where the relative efficiency, size and weight advantages of devices based on high-temperature superconductivity outweigh the additional costs involved.

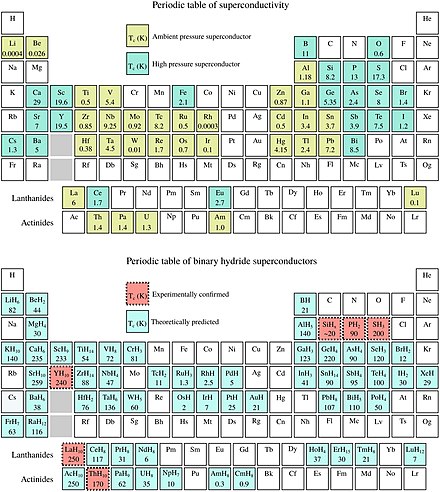

Bottom: Periodic table of superconducting binary hydrides (0–300 GPa). Theoretical predictions indicated in blue and experimental results in red [ 39 ]

-

BCS (dark green circle)

-

Heavy fermion-based (light green star)

-

Cuprate (blue diamond)

-

Buckminsterfullerene -based (purple inverted triangle)

-

Strontium ruthenate (grey pentagon)

-

Nickel -based (pink six-point star)