Electrolysis of water

[2] In 1789, Jan Rudolph Deiman and Adriaan Paets van Troostwijk used an electrostatic machine to make electricity that was discharged on gold electrodes in a Leyden jar.

[3] In 1800, Alessandro Volta invented the voltaic pile, while a few weeks later English scientists William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle used it to electrolyse water.

In 1806 Humphry Davy reported the results of extensive distilled water electrolysis experiments, concluding that nitric acid was produced at the anode from dissolved atmospheric nitrogen.

[5] A DC electrical power source is connected to two electrodes, or two plates (typically made from an inert metal such as platinum or iridium) that are placed in the water.

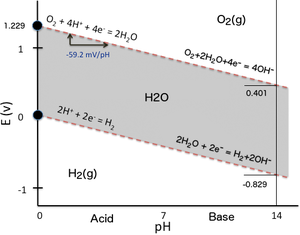

[citation needed] Electrolysis of pure water requires excess energy in the form of overpotential to overcome various activation barriers.

Therefore, activation energy, ion mobility (diffusion) and concentration, wire resistance, surface hindrance including bubble formation (blocks electrode area), and entropy, require greater potential to overcome.

In this case, the two half-reactions are coupled and limited by electron-transfer steps (the electrolysis current is saturated at shorter electrode distances).

However, this configuration has challenges such as the potential for Cl ions to pass through the membrane and cause damage, as well as the risk of hydrogen and oxygen mixing without a separator.

This method combines a hydrophobic porous polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) waterproof breathable membrane with a self-dampening electrolyte, utilizing a hygroscopic sulfuric acid solution with a commercial alkaline electrolyzer to generate hydrogen gas from seawater.

A platinum electrode (plate or honeycomb) is placed at the bottom of each of the two side cylinders, connected to the terminals of an electricity source.

The first large-scale demand for hydrogen emerged in late 19th century for lighter-than-air aircraft, and before the advent of steam reforming in the 1930s, the technique was competitive.

[citation needed] Hydrogen-based technologies have evolved significantly since the initial discovery of hydrogen and its early application as a buoyant gas approximately 250 years ago.

This prototype, equipped with a four-wheel design, utilised an internal combustion engine (ICE) fuelled by a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen gases.

This invention could be viewed as an early embodiment of a system comprising hydrogen storage, conduits, valves, and a conversion device.

PEM fuel cells use a solid polymer membrane (a thin plastic film) which is permeable to hydrogen ions (protons) when it is saturated with water, but does not conduct electrons.

[43] PEM fuel cells use a solid polymer membrane (a thin plastic film) that is permeable to protons when saturated with water, but does not conduct electrons.

Benefits include improved electrical efficiency, >221bar pressurised delivery of product gases, ability to operate at high current densities and low dependence on precious metal catalysts.

[54] In 2017, researchers reported nanogap electrochemical cells that achieved high-efficiency electrolyte-free pure water electrolysis at ambient temperature.

Its "Virtual Breakdown Mechanism", is completely different from traditional electrochemical theory, due to such nanogap size effects.

The vast majority of current industrial hydrogen production is from natural gas in the steam reforming process, or from the partial oxidation of coal or heavy hydrocarbons.

The hydrogen produced from this process is either burned (converting it back to water), used for the production of specialty chemicals, or various other small-scale applications.

Solid oxide electrolyzer cells (SOEC) are the third most common type of electrolysis, and the most expensive, and use high operating temperatures to increase efficiency.

To assess the claimed efficiency of an electrolyzer it is important to establish how it was defined by the vendor (i.e. what enthalpy value, what current density, etc.).

[68] In 2024, Australian company Hysata announced a device capable of 95% efficiency relative to the higher heating value of hydrogen.

The US DOE target price for hydrogen in 2020 is $2.30/kg, requiring an electricity cost of $0.037/kW·h, which is achievable given 2018 PPA tenders[76] for wind and solar in many regions.

This puts the $4/gasoline gallon equivalent (gge) H2 dispensed objective well within reach, and close to a slightly elevated natural gas production cost for SMR.

The large price increase of gas during the 2021–2022 global energy crisis made hydrogen electrolysis economic in some parts of the world.

Developing a cheap, effective electrocatalyst for this reaction would be a great advance, and is a topic of current research; there are many approaches, among them a 30-year-old recipe for molybdenum sulfide,[84] graphene quantum dots,[85] carbon nanotubes,[52] perovskite,[86] and nickel/nickel-oxide.

[87][88] Trimolybdenum phosphide (Mo3P) has been recently found as a promising nonprecious metal and earth‐abundant candidate with outstanding catalytic properties that can be used for electrocatalytic processes.

[89][90] The simpler two-electron reaction to produce hydrogen at the cathode can be electrocatalyzed with almost no overpotential by platinum, or in theory a hydrogenase enzyme.

60% efficient at 1000° C

Steam reforming of hydrocarbons to hydrogen is 70-85% efficient [ 35 ]