Electron

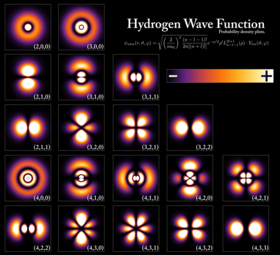

[15] Quantum mechanical properties of the electron include an intrinsic angular momentum (spin) of a half-integer value, expressed in units of the reduced Planck constant, ħ.

Electrons play an essential role in numerous physical phenomena, such as electricity, magnetism, chemistry, and thermal conductivity; they also participate in gravitational, electromagnetic, and weak interactions.

[17] In 1838, British natural philosopher Richard Laming first hypothesized the concept of an indivisible quantity of electric charge to explain the chemical properties of atoms.

[18] In his 1600 treatise De Magnete, the English scientist William Gilbert coined the Neo-Latin term electrica, to refer to those substances with property similar to that of amber which attract small objects after being rubbed.

[23] Between 1838 and 1851, British natural philosopher Richard Laming developed the idea that an atom is composed of a core of matter surrounded by subatomic particles that had unit electric charges.

[2] Beginning in 1846, German physicist Wilhelm Eduard Weber theorized that electricity was composed of positively and negatively charged fluids, and their interaction was governed by the inverse square law.

After studying the phenomenon of electrolysis in 1874, Irish physicist George Johnstone Stoney suggested that there existed a "single definite quantity of electricity", the charge of a monovalent ion.

In 1881, German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz argued that both positive and negative charges were divided into elementary parts, each of which "behaves like atoms of electricity".

[33] In 1879, he proposed that these properties could be explained by regarding cathode rays as composed of negatively charged gaseous molecules in a fourth state of matter, in which the mean free path of the particles is so long that collisions may be ignored.

[34]: 394–395 In 1883, not yet well-known German physicist Heinrich Hertz tried to prove that cathode rays are electrically neutral and got what he interpreted as a confident absence of deflection in electrostatic, as opposed to magnetic, field.

However, as J. J. Thomson explained in 1897, Hertz placed the deflecting electrodes in a highly-conductive area of the tube, resulting in a strong screening effect close to their surface.

[38] While studying naturally fluorescing minerals in 1896, the French physicist Henri Becquerel discovered that they emitted radiation without any exposure to an external energy source.

[41][42] In 1897, the British physicist J. J. Thomson, with his colleagues John S. Townsend and H. A. Wilson, performed experiments indicating that cathode rays really were unique particles, rather than waves, atoms or molecules as was believed earlier.

[47][26] The electron's charge was more carefully measured by the American physicists Robert Millikan and Harvey Fletcher in their oil-drop experiment of 1909, the results of which were published in 1911.

[49] Around the beginning of the twentieth century, it was found that under certain conditions a fast-moving charged particle caused a condensation of supersaturated water vapor along its path.

[50] By 1914, experiments by physicists Ernest Rutherford, Henry Moseley, James Franck and Gustav Hertz had largely established the structure of an atom as a dense nucleus of positive charge surrounded by lower-mass electrons.

[54] In 1919, the American chemist Irving Langmuir elaborated on the Lewis's static model of the atom and suggested that all electrons were distributed in successive "concentric (nearly) spherical shells, all of equal thickness".

[57] The physical mechanism to explain the fourth parameter, which had two distinct possible values, was provided by the Dutch physicists Samuel Goudsmit and George Uhlenbeck.

About the same time, Polykarp Kusch, working with Henry M. Foley, discovered the magnetic moment of the electron is slightly larger than predicted by Dirac's theory.

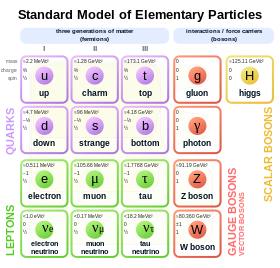

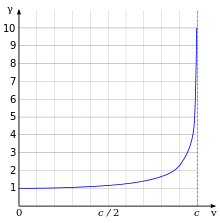

[74] The Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) at CERN, which was operational from 1989 to 2000, achieved collision energies of 209 GeV and made important measurements for the Standard Model of particle physics.

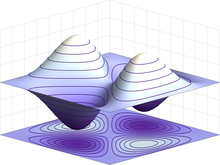

[101] The combination of the energy variation needed to create these particles, and the time during which they exist, fall under the threshold of detectability expressed by the Heisenberg uncertainty relation, ΔE · Δt ≥ ħ.

In effect, the energy needed to create these virtual particles, ΔE, can be "borrowed" from the vacuum for a period of time, Δt, so that their product is no more than the reduced Planck constant, ħ ≈ 6.6×10−16 eV·s.

[119][120] On the other hand, a high-energy photon can transform into an electron and a positron by a process called pair production, but only in the presence of a nearby charged particle, such as a nucleus.

[140] When cooled below a point called the critical temperature, materials can undergo a phase transition in which they lose all resistivity to electric current, in a process known as superconductivity.

Electrons inside conducting solids, which are quasi-particles themselves, when tightly confined at temperatures close to absolute zero, behave as though they had split into three other quasiparticles: spinons, orbitons and holons.

[151][152] The surviving protons and neutrons began to participate in reactions with each other—in the process known as nucleosynthesis, forming isotopes of hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of lithium.

[158] According to classical physics, these massive stellar objects exert a gravitational attraction that is strong enough to prevent anything, even electromagnetic radiation, from escaping past the Schwarzschild radius.

When a pair of virtual particles (such as an electron and positron) is created in the vicinity of the event horizon, random spatial positioning might result in one of them to appear on the exterior; this process is called quantum tunnelling.

[166][167] In laboratory conditions, the interactions of individual electrons can be observed by means of particle detectors, which allow measurement of specific properties such as energy, spin and charge.

[192][193][194] In the free-electron laser (FEL), a relativistic electron beam passes through a pair of undulators that contain arrays of dipole magnets whose fields point in alternating directions.