Electrospinning

Electrospinning is a fiber production method that uses electrical force (based on electrohydrodynamic[1] principles) to draw charged threads of polymer solutions for producing nanofibers with diameters ranging from nanometers to micrometers.

[4][5] As the jet dries in flight, the mode of current flow changes from ohmic to convective as the charge migrates to the surface of the fiber.

The jet is then elongated by a whipping process caused by electrostatic repulsion initiated at small bends in the fiber, until it is finally deposited on the grounded collector.

Electrospun fibers can adopt a porous or core–shell morphology depending on the type of materials being spun as well as the evaporation rates and miscibility for the solvents involved.

For techniques which involve multiple spinning fluids, the general criteria for the creation of fibers depends upon the spinnability of the outer solution.

[29] This opens up the possibility of creating composite fibers which can function as drug delivery systems or possess the ability to self-heal upon failure.

However, these fibers are typically more difficult to produce compared to coaxial spinning due to the greater number of variables which must be accounted for in creating the emulsion.

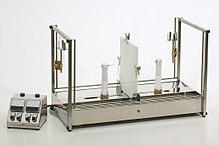

The setup is very similar to that employed in conventional electrospinning and includes the use of a syringe or spinneret, a high voltage supply and the collector.

[36] Due to the high viscosity of polymer melts, the fiber diameters are usually slightly larger than those obtained from solution electrospinning.

The most significant factors which affect the fiber size tend to be the feed rate, the molecular weight of the polymer and the diameter of the spinneret.

[39] He found that as his stock liquid reached the edge of the dish, that he could draw fibers from a number of materials including shellac, beeswax, sealing-wax, gutta-percha and collodion.

[53] Simon, in a 1988 NIH SBIR grant report, showed that solution electrospinning could be used to produce nano- and submicron-scale polystyrene and polycarbonate fibrous mats specifically intended for use as in vitro cell substrates.

[54] In the early 1990s several research groups (notably that of Reneker and Rutledge who popularised the name electrospinning for the process)[55] demonstrated that many organic polymers could be electrospun into nanofibers.

Between 1996 and 2003 the interest in electrospinning underwent an explosive growth, with the number of publications and patent applications approximately doubling every year.

[58] In addition to this, the ultra-fine fibers produced by electrospinning are expected to have two main properties, a very high surface to volume ratio, and a relatively defect free structure at the molecular level.

Since the essential properties of protective clothing are high moisture vapor transport, increased fabric breath-ability, and enhanced toxic chemical resistance, electrospun nanofiber membranes are good candidates for these applications.

For example, iron oxide nanoparticles, a good arsenic adsorbent, can be trapped within poly(vinyl alcohol) electrospun nanofibers for water remmediation.

[61] The majority of early patents for electrospinning were for textile applications, however little woven fabric was actually produced, perhaps due to difficulties in handling the barely visible fibers.

[64] The electrospun scaffolds made for tissue engineering applications can be penetrated with cells to treat or replace biological targets.

[73] Interestingly, electrospinning allows to fabricate nanofibers with advanced architecture [74] that can be used to promote the delivery of multiple drugs at the same time and with different kinetics.

[78] The synthesized liquid drug can be quickly turned into an electrospun solid product processable for tableting and other dosage forms.

Electrospinning is being investigated as a source of cost-effective, easy to manufacture wound dressings, medical implants, and scaffolds for the production of artificial human tissues.