Eliminative materialism

[1] Some supporters of eliminativism argue that no coherent neural basis will be found for many everyday psychological concepts such as belief or desire, since they are poorly defined.

Eliminative materialism is the relatively new (1960s–70s) idea that certain classes of mental entities that common sense takes for granted, such as beliefs, desires, and the subjective sensation of pain, do not exist.

[9] An intermediate position, revisionary materialism, often argues the mental state in question will prove to be somewhat reducible to physical phenomena—with some changes needed to the commonsense concept.

[1][10] Since eliminative materialism arguably claims that future research will fail to find a neuronal basis for various mental phenomena, it may need to wait for science to progress further.

One might question the position on these grounds, but philosophers like Churchland argue that eliminativism is often necessary in order to open the minds of thinkers to new evidence and better explanations.

Eliminativists argue that commonsense "folk" psychology has failed and will eventually need to be replaced by explanations derived from neuroscience.

[15] Eliminativism maintains that the commonsense understanding of the mind is mistaken, and that neuroscience will one day reveal that mental states talked about in everyday discourse, using words such as "intend", "believe", "desire", and "love", do not refer to anything real.

But critics pointed out that eliminativists could not have it both ways: either mental states exist and will ultimately be explained in terms of lower-level neurophysiological processes, or they do not.

Radical behaviorists, such as Skinner, argued that folk psychology is already obsolete and should be replaced by descriptions of histories of reinforcement and punishment.

[8] Eliminativists such as Paul and Patricia Churchland argue that folk psychology is a fully developed but non-formalized theory of human behavior.

As a theory in the scientific sense, eliminativists maintain, folk psychology must be evaluated on the basis of its predictive power and explanatory success as a research program for the investigation of the mind/brain.

They argue that folk psychology excludes from its purview or has traditionally been mistaken about many important mental phenomena that can and are being examined and explained by modern neuroscience.

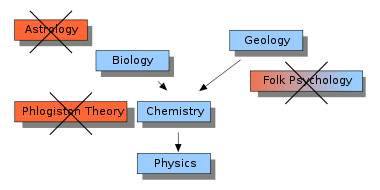

[34] Another line of argument is the meta-induction based on what eliminativists view as the disastrous historical record of folk theories in general.

[33] Indeed, the eliminativists warn, considerations of intuitive plausibility may be precisely the result of the deeply entrenched nature in society of folk psychology itself.

An example of this is the language of thought hypothesis, which attributes a discrete, combinatorial syntax and other linguistic properties to these mental phenomena.

Eliminativists argue that such discrete, combinatorial characteristics have no place in neuroscience, which speaks of action potentials, spiking frequencies, and other continuous and distributed effects.

[44][45] Eliminativists argue that if natural selection—the process responsible for shaping our neural architecture—cannot solve the disjunction problem, then our brains cannot store unique, non-disjunctive propositions, as required by folk psychology.

This argument leads eliminativists to reject the notion that neural states have specific, determinate informational content corresponding to the discrete, non-disjunctive propositions of folk psychology.

This evolutionary argument adds to the eliminativist case that our commonsense understanding of beliefs, desires, and other propositional attitudes is flawed and should be replaced by a neuroscientific account that acknowledges the indeterminate nature of neural representations.

The thesis of eliminativism seems so obviously wrong to many critics, who find it undeniable that people know immediately and indubitably that they have minds, that argumentation seems unnecessary.

Analogies from the history of science are frequently invoked to buttress this observation: it may appear obvious that the sun travels around the earth, for example, but this was nevertheless proved wrong.

[50] Some philosophers, such as Paul Boghossian, have attempted to show that eliminativism is in some sense self-refuting, since the theory presupposes the existence of mental phenomena.

[15][52] Georges Rey and Michael Devitt reply to this objection by invoking deflationary semantic theories that avoid analyzing predicates like "x is true" as expressing a real property.

This way, Rey and Devitt argue, insofar as dispositional replacements of "claims" and deflationary accounts of "true" are coherent, eliminativism is not self-refuting.

Neuroscientists use the word "representation" to identify the neural circuits' encoding of inputs from the peripheral nervous system in, for example, the visual cortex.

Subsequent research into neural processing has increasingly vindicated a structural resemblance or physical isomorphism approach to how information enters the brain and is stored and deployed.

Another approach argues that the pragmatic theory of truth should be used from the start to decide whether certain neural circuits store true information about the external world.

Although not advocates of eliminativism, John Shook and Tibor Solymosi argue that pragmatism is a promising program for understanding advancements in neuroscience and integrating them into a philosophical picture of the world.

[12][13] Jerry Fodor believes in folk psychology's success as a theory, because it makes for an effective way of communication in everyday life that can be implemented with few words.

Influenced by Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations, Dennett and Rey have defended eliminativism about qualia even when other aspects of the mental are accepted.