Chemical equilibrium

However, the law of mass action is valid only for concerted one-step reactions that proceed through a single transition state and is not valid in general because rate equations do not, in general, follow the stoichiometry of the reaction as Guldberg and Waage had proposed (see, for example, nucleophilic aliphatic substitution by SN1 or reaction of hydrogen and bromine to form hydrogen bromide).

[2][6] Although the macroscopic equilibrium concentrations are constant in time, reactions do occur at the molecular level.

Le Châtelier's principle (1884) predicts the behavior of an equilibrium system when changes to its reaction conditions occur.

What this means is that the derivative of the Gibbs energy with respect to reaction coordinate (a measure of the extent of reaction that has occurred, ranging from zero for all reactants to a maximum for all products) vanishes (because dG = 0), signaling a stationary point.

When the reactants are dissolved in a medium of high ionic strength the quotient of activity coefficients may be taken to be constant.

For this reason, equilibrium constants for solutions are usually determined in media of high ionic strength.

The constant volume case is important in geochemistry and atmospheric chemistry where pressure variations are significant.

Note that, if reactants and products were in standard state (completely pure), then there would be no reversibility and no equilibrium.

The mixing of the products and reactants contributes a large entropy increase (known as entropy of mixing) to states containing equal mixture of products and reactants and gives rise to a distinctive minimum in the Gibbs energy as a function of the extent of reaction.

The relation between the Gibbs free energy and the equilibrium constant can be found by considering chemical potentials.

[1] At constant temperature and pressure in the absence of an applied voltage, the Gibbs free energy, G, for the reaction depends only on the extent of reaction: ξ (Greek letter xi), and can only decrease according to the second law of thermodynamics.

In order to meet the thermodynamic condition for equilibrium, the Gibbs energy must be stationary, meaning that the derivative of G with respect to the extent of reaction, ξ, must be zero.

At constant pressure and temperature the above equations can be written as which is the Gibbs free energy change for the reaction.

This results in: By substituting the chemical potentials: the relationship becomes: which is the standard Gibbs energy change for the reaction that can be calculated using thermodynamical tables.

In the real world, for example, when making ammonia in industry, fugacity coefficients must be taken into account.

[citation needed] In aqueous solution, equilibrium constants are usually determined in the presence of an "inert" electrolyte such as sodium nitrate, NaNO3, or potassium perchlorate, KClO4.

When the concentration of dissolved salt is much higher than the analytical concentrations of the reagents, the ions originating from the dissolved salt determine the ionic strength, and the ionic strength is effectively constant.

When pure substances (liquids or solids) are involved in equilibria their activities do not appear in the equilibrium constant[14] because their numerical values are considered one.

Applying the general formula for an equilibrium constant to the specific case of a dilute solution of acetic acid in water one obtains For all but very concentrated solutions, the water can be considered a "pure" liquid, and therefore it has an activity of one.

Most commonly [OH−] is replaced by Kw[H+]−1 in equilibrium constant expressions which would otherwise include hydroxide ion.

An example is the Boudouard reaction:[14] for which the equation (without solid carbon) is written as: Consider the case of a dibasic acid H2A.

An alternative formulation is At first sight this appears to offer a means of obtaining the standard molar enthalpy of the reaction by studying the variation of K with temperature.

For example, see ICE table for a traditional method of calculating the pH of a solution of a weak acid.

For instance, in the case of a dibasic acid, H2A dissolved in water the two reactants can be specified as the conjugate base, A2−, and the proton, H+.

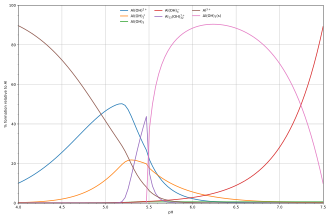

The diagram above illustrates the point that a precipitate that is not one of the main species in the solution equilibrium may be formed.

Another common instance where precipitation occurs is when a metal cation interacts with an anionic ligand to form an electrically neutral complex.

is the chemical potential in the standard state, R is the gas constant T is the absolute temperature, and Aj is the activity.

If ions are involved, an additional row is added to the aij matrix specifying the respective charge on each molecule which will sum to zero.

This allows each of the Nj and λj to be treated independently, and it can be shown using the tools of multivariate calculus that the equilibrium condition is given by (For proof see Lagrange multipliers.)

This method of calculating equilibrium chemical concentrations is useful for systems with a large number of different molecules.