Ernest Lawrence

[2] Lawrence attended the public schools of Canton and Pierre, then enrolled at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, but transferred after a year to the University of South Dakota in Vermillion.

Reducing the emission time by switching the light source on and off rapidly made the spectrum of energy emitted broader, in conformance with Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.

Lawrence chose to stay at the more prestigious Yale,[13] but because he had never been an instructor, the appointment was resented by some of his fellow faculty, and in the eyes of many it still did not compensate for his South Dakota immigrant background.

[8] Based on Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie's 1934 published work on artificial radioactivity, Lawrence discovered the nitrogen-13 isotope by firing high-energy protons into a carbon-13 element in his laboratory.

[15] He and his team including Martin Kamen and Samuel Ruben accidentally discovered the carbon-14 isotope by bombarding graphite with high-energy protons.

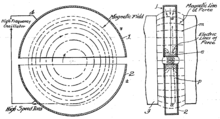

The magnetic field would hold the charged protons in a spiral path as they were accelerated between just two semicircular electrodes connected to an alternating potential.

Their first cyclotron was made out of brass, wire, and sealing wax and was only four inches (10 cm) in diameter—it could be held in one hand, and probably cost a total of $25 (equivalent to $600 in 2023).

In April 1932, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton at the Cavendish Laboratory in England announced that they had bombarded lithium with protons and succeeded in transmuting it into helium.

[43] Lawrence employed a simple business model: "He staffed his laboratory with graduate students and junior faculty of the physics department, with fresh Ph.D.s willing to work for anything, and with fellowship holders and wealthy guests able to serve for nothing.

Working with his brother John and Israel Lyon Chaikoff from the University of California's physiology department, Lawrence supported research into the use of radioactive isotopes for therapeutic purposes.

[53] Lawrence was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in November 1939 "for the invention and development of the cyclotron and for results obtained with it, especially with regard to artificial radioactive elements".

The Nobel award ceremony was held on February 29, 1940, in Berkeley, California, due to World War II, in the auditorium of Wheeler Hall on the campus of the university.

He helped recruit staff for the MIT Radiation Laboratory, where American physicists developed the cavity magnetron invented by Mark Oliphant's team in Britain.

In December 1940, Glenn T. Seaborg and Emilio Segrè used the 60-inch (150 cm) cyclotron to bombard uranium-238 with deuterons producing a new element, neptunium-238, which decayed by beta emission to form plutonium-238.

Oliphant, in turn, took the Americans to task for not following up the recommendations of the British MAUD Committee, which advocated a program to develop an atomic bomb.

[65] On his recommendation, the director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves Jr., appointed Oppenheimer as head of its Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico.

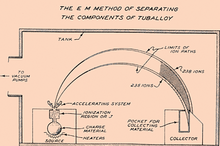

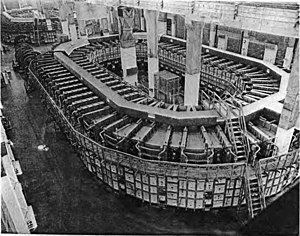

[67] Responsibility for the design and construction of the electromagnetic separation plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which came to be called Y-12, was assigned to Stone & Webster.

[72] When the plant was started up for testing on schedule in October 1943, the 14-ton vacuum tanks crept out of alignment because of the power of the magnets and had to be fastened more securely.

[76] Lawrence hoped that the Manhattan Project would develop improved calutrons and construct Alpha III racetracks, but they were judged to be uneconomical.

Groves approved the money, but cut a number of programs, including Seaborg's proposal for a "hot" radiation laboratory in densely populated Berkeley, and John Lawrence's for production of medical isotopes, because this need could now be better met from nuclear reactors.

He had a most unusual intuitive approach to involved physical problems, and when explaining new ideas to him, one quickly learned not to befog the issue by writing down the differential equation that might appear to clarify the situation.

[85] For the first time since 1935, Lawrence actively participated in the experiments, working with Eugene Gardner in an unsuccessful attempt to create recently discovered pi mesons with the synchrotron.

After some negotiation, the university agreed to extend the contract for what was now the Los Alamos National Laboratory for four more years and to appoint Norris Bradbury, who had replaced Oppenheimer as its director in October 1945, as a professor.

[91] In the chilly Cold War climate of the post-war University of California, Lawrence accepted the House Un-American Activities Committee's actions as legitimate, and did not see them as indicative of a systemic problem involving academic freedom or human rights.

[91] He was forced to defend Radiation Laboratory staff members like Robert Serber who were investigated by the university's Personnel Security Board.

Lawrence and Teller had to argue their case not only with the Atomic Energy Commission, which did not want it, and the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which was implacably opposed but with proponents who felt that Chicago was the more obvious site for it.

By this time, the Atomic Energy Commission had spent $45 million on the Mark I, which had commenced operation, but was mainly used to produce polonium for the nuclear weapons program.

[106] In July 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked Lawrence to travel to Geneva, Switzerland, to help negotiate a proposed Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union.

[107] Despite suffering from a serious flare-up of his chronic ulcerative colitis, Lawrence decided to go, but he became ill while in Geneva, and was rushed back to the hospital at Stanford University.

After him, massive industrial, and especially governmental, expenditures of manpower and monetary funding made "big science," carried out by large-scale research teams, a major segment of the national economy.