Demographics of Mexico

Although this tendency has been reversed and average annual population growth over the last five years was less than 1%, the demographic transition is still in progress; Mexico still has a large youth cohort.

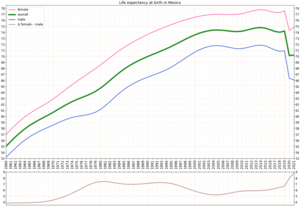

[15] During the period of economic prosperity that was dubbed by economists as the "Mexican Miracle", the government invested in efficient social programs that reduced the infant mortality rate and increased life expectancy.

Since the adoption of NAFTA in 1994, however, which allows all products to be imported duty-free regardless of their place of origin within Mexico, the non-border maquiladora share of exports has increased while that of border cities has decreased.

[21] After decades of the gap narrowing, in 2020 the fertility rate in Mexico fell below the United States for the first time falling 22% in 2020 and a further 10.5% in the first half of 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Assumptions underlying this projection include fertility stabilizing at 1.85 children per woman and continued high net emigration (slowly decreasing from 583,000 in 2005 to 393,000 in 2050).

[41] The PRI governments, in power for most of the 20th century, had a policy of granting asylum to fellow Latin Americans fleeing political persecution in their home countries.

[42][43] Due to the 2008 Financial Crisis and the resulting economic decline and high unemployment in Spain, many Spaniards have been emigrating to Mexico to seek new opportunities.

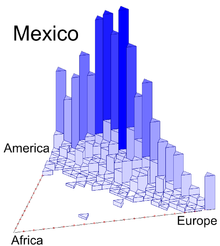

[51] The great majority of Mexican emigrants have moved to the United States of America, this migration phenomenon has been a defining feature in the relationship of both countries for most of the 20th century.

[98] This is the product of an ideology strongly promoted by Mexican academics such as Manuel Gamio and José Vasconcelos known as mestizaje, whose goal was that of Mexico becoming a racially and culturally homogeneous country.

[135][132][109] Newer publications that do cite Aguirre-Beltran's work take those factors into consideration, stating that the Spaniard/Euromestizo/Criollo ethnic label was composed on its majority by descendants of Europeans, albeit the category may have included people with some non-European ancestry.

According to these criteria, the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, or CDI in Spanish) and the INEGI (Mexico's National Institute of Statistics and Geography), state that there are 15.7 million indigenous people in Mexico of many different ethnic groups,[144] which constitute 14.9% of the population in the country,[145] with 1.2% not speaking Spanish.

According to 20th- and 21st-century academics, large scale intermixing between the European immigrants and the native Indigenous peoples would produce a Mestizo group which would become the overwhelming majority of Mexico's population by the time of the Mexican Revolution.

[178] Some communities of European immigrants have remained isolated from the rest of the general population since their arrival, among them the German-speaking Mennonites from Russia of Chihuahua and Durango,[179] and the Venetos of Chipilo, Puebla, which have retained their original languages.

The existence of individuals of Sub-Saharan African descent in Mexico has its origins in the slave trade that took place during colonial times and that did not end until 1829 after the consummation of the Mexican independence.

Mexican President Anastasio Bustamante, concerned that the US would annex Texas, sought to limit Anglo-American immigration in 1830 and mandated no new slaves in the territory.

[40] Immigration of Arabs in Mexico has influenced Mexican culture, in particular food, where they have introduced Kibbeh, Tabbouleh and even created recipes such as Tacos Árabes.

in cities of Mexicali in the Imperial Valley U.S./Mexico, and Tijuana across from San Diego with a large Arab American community (about 280,000), some of whose families have relatives in Mexico.

Today, the most common Arabic surnames in Mexico include Nader, Hayek, Ali, Haddad, Nasser, Malik, Abed, Mansoor, Harb, and Elias.

For two and a half centuries, between 1565 and 1815, many Filipinos and Mexicans sailed back and forth between Mexico and the Philippines as crews, prisoners, adventurers and soldiers in the Manila-Acapulco Galleon assisting Spain in its trade between Asia and the Americas.

Also, on these voyages, thousands of Asian individuals (mostly males) were brought to Mexico as slaves and were called "Chino",[190] which means Chinese, although in reality they were of diverse origins, including Koreans, Japanese, Malays, Filipinos, Javanese, Cambodians, Timorese, and people from Bengal, India, Ceylon, Makassar, Tidore, Terenate, and China.

[191][192][193] A notable example is the story of Catarina de San Juan (Mirra), an Indian girl captured by the Portuguese and sold into slavery in Manila.

The indigenous people were legally protected from chattel slavery, and by being recognized as part of this group, Asian slaves could claim they were wrongly enslaved.

Most of its original datasets have reportedly been lost, so most of what is known about it nowadays comes from essays and field investigations made by academics who had access to the census data and used it as reference for their works, such as Prussian geographer Alexander von Humboldt.

Each author gives different estimations for each racial group in the country although they do not vary greatly, with Europeans ranging from 18% to 22% of New Spain's population, Mestizos from 21% to 25%, Indians from 51% to 61%, and Africans from 6,000 and 10,000.

Regardless of the possible inaccuracies related to the counting of Indigenous peoples living outside of the colonized areas, the effort that New Spain's authorities put into considering them as subjects is worth mentioning, as censuses made by other colonial or post-colonial countries did not consider American Indians to be citizens or subjects; for example, the censuses made by the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata would only count the inhabitants of the colonized settlements.

[201] It is claimed that the mestizaje process sponsored by the state was more "cultural than biological", which resulted in the numbers of the Mestizo Mexican group being inflated at the expense of the identity of other races.

[207] Even though nowadays the large majority of the country's population consider themselves Mexicans, differences on physical features and appearance continue playing an important role on everyday social interactions,[208][119] taking this into account, on recent time Mexico's government has begun conducting ethnic investigations to cuantify the different ethnic groups that inhabit the country with the aim of reducing social inequalities between them.

Generally speaking ethnic relations can be arranged on an axis between the two extremes of European and Amerindian cultural heritage, this is a remnant of the Spanish caste system which categorized individuals according to their perceived level of biological mixture between the two groups although in practice the classificatory system has become fluid, mixing socio-cultural traits with phenotypical traits allowing individuals to move between categories and define their ethnic and racial identities situationally,[213] the presence of considerable portions of the population with African and Asian heritage makes the situation more complex.

[207] The lack of a clear dividing line between white and mixed race Mexicans has made the concept of race relatively fluid, with descent being more of a determining factor than biological traits,[151][207] however contemporary sociologists and historians agree that, given that the concept of "race" has a psychological foundation rather than a biological one and to society's eyes a Mestizo with a high percentage of European ancestry is considered "white" and a Mestizo with a high percentage of Indigenous ancestry is considered "Indian", a person who identifies with a given ethnic group should be allowed to, even if biologically that person does not completely belong to that group.

Since 1857 with the La Reforma laws, the Mexican Constitution drastically separates Church and State, unlike some other countries in Latin America or Ibero-America.