Ethylene (plant hormone)

[5] Commercial fruit-ripening rooms use "catalytic generators" to make ethylene gas from a liquid supply of ethanol.

In the 19th century, city dwellers noticed that gas leaks from street lights led to stunting of growth, death of flowers and premature leaf fall.

In 1896, Russian botanist Dimitry Neljubow studied the response pea to illuminating gas to which they showed movement.

[15] Reporting in Nature that ripe fruit (in this case Worcester Pearmain apple) produced ethylene he said:The amount of ethylene produced [by the apple] is very small—perhaps of the order of 1 cubic centimetre during the whole life-history of the fruit; and the cause of its prodigious biological activity in such small concentration is a problem for further research.

[16] He subsequently showed that ethylene was produced by other fruits as well, and that obtained from apple could induce seed germination and plant growth in different vegetables (but not in cereals).

[2] They became more convincing when William Crocker, Alfred Hitchcock, and Percy Zimmerman reported in 1935 that ethylene acts similar to auxins in causing plant growth and senescence of vegetative tissues.

[18][19] Ethylene is produced from essentially all parts of higher plants, including leaves, stems, roots, flowers, fruits, tubers, and seeds.

During the life of the plant, ethylene production is induced during certain stages of growth such as germination, ripening of fruits, abscission of leaves, and senescence of flowers.

Ethylene production can also be induced by a variety of external aspects such as mechanical wounding, environmental stresses, and certain chemicals including auxin and other regulators.

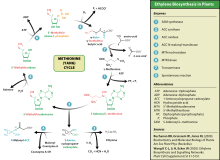

Ethylene is biosynthesized from the amino acid methionine to S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM, also called Adomet) by the enzyme Met adenosyltransferase.

Dominant missense mutations in any of the gene family, which comprises five gasoreceptors in Arabidopsis and at least six in tomato, can confer insensitivity to ethylene.

[22] Loss-of-function mutations in multiple members of the ethylene-gasoreceptor family result in a plant that exhibits constitutive ethylene responses.

The osmotic pressure in the plant is what maintains water uptake and cell turgor to help with stomatal function and other cellular mechanisms.

Ethylene is known for regulating plant growth and development and adapted to stress conditions through a complex signal transduction pathway.

Environmental cues such as flooding, drought, chilling, wounding, and pathogen attack can induce ethylene formation in plants.

The development of the corolla is directed in part by ethylene, though its concentration is highest when the plant is fertilized and no longer requires the production or maintenance of structures and compounds that attract pollinators.

Ethylene's role in this developmental scenario is to move the plant away from a state of attracting pollinators, so it also aids in decreasing the production of these volatiles.

While the mechanism of ethylene-mediated senescence are unclear, its role as a senescence-directing hormone can be confirmed by ethylene-sensitive petunia response to ethylene knockdown.

Flowers and plants which are subjected to stress during shipping, handling, or storage produce ethylene causing a significant reduction in floral display.