Etruscan religion

Odysseus, Menelaus and Diomedes from the Homeric tradition were recast in tales of the distant past that had them roaming the lands West of Greece.

In the last years of the Roman Republic the religion began to fall out of favor and was satirized by such notable public figures as Marcus Tullius Cicero.

The Julio-Claudians, especially Claudius, whose first wife, Plautia Urgulanilla, claimed an Etruscan descent,[5] maintained a knowledge of the language and religion for a short time longer,[6] but this practice soon ceased.

A number of canonical works in the Etruscan language survived until the middle of the first millennium AD, but were destroyed by the ravages of time, including occasional catastrophic fires, and by decree of the Roman Senate.

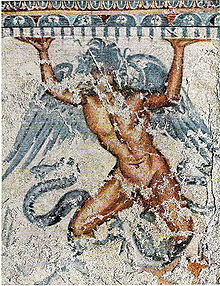

[citation needed] The mythology is evidenced by a number of sources in different media, for example representations on large numbers of pottery items, inscriptions and engraved scenes on the Praenestine cistae (ornate boxes; see under Etruscan language) and on specula (ornate hand mirrors).

Divinatory inquiries according to discipline were conducted by priests whom the Romans called haruspices or sacerdotes; Tarquinii had a college of 60 of them.

[13] The Etruscans, as evidenced by the inscriptions, used several words: capen (Sabine cupencus), maru (Umbrian maron-), eisnev, hatrencu (priestess).

[15] In several instances of Etruscan art, such as in the François Tomb in Vulci, a spirit of the dead is identified by the term hinthial, literally "(one who is) underneath".

)[17] Ruling over them were higher deities that seem to reflect the Indo-European system: Tin or Tinia, the sky, Uni his wife (Juno), Nethuns, god of the waters, and Cel, the earth goddess.

[17] A fourth group, the so-called dii involuti or "veiled gods", are sometimes mentioned as superior to all the other deities, but these were never worshipped, named, or depicted directly.

[20] Etruscan tombs imitated domestic structures and were characterized by spacious chambers, wall paintings and grave furniture.

[citation needed] It was ruled by Aita, and the deceased was guided there by Charun, the equivalent of Death, who was blue and wielded a hammer.

For example, the husband and wife often stood alongside each other in representations, and women were portrayed on sarcophagi in the same ceremonial feasts that men were.

[23] An inscribed bronze statue base dating to the Archaic period (525-500 BCE) was excavated at Campo della Fiera in Orvieto, Italy, and provides evidence of an affluent woman's offering to a deity.

[27] The role of the hatrencu is thought to be similar to that of the Roman college of matrons, which was dedicated to the worship of the goddess Mater Matuta.

[26] Whether there were female religious specialists such as Etruscan priestess in Etruria, is mainly speculation and is subject to ongoing academic debate.