Etruscan sculpture

[1] Given the almost total lack of Etruscan written documents, a problem compounded by the paucity of information on their language—still largely undeciphered—it is in their art that the keys to the reconstruction of their history are to be found, although Greek and Roman chronicles are also of great help.

Like its culture in general, Etruscan sculpture has many obscure aspects for scholars, being the subject of controversy and forcing them to propose their interpretations always tentatively, but the consensus is that it was part of the most important and original legacy of Italian art and even contributed significantly to the initial formation of the artistic traditions of ancient Rome.

[6] What is known with certainty is that by the middle of the 7th century BC their main cities had already been founded, beginning immediately a period of territorial expansion that ended up dominating a large region more or less in the center of the Italic peninsula, ranging from Veneto and Lombardy to Latium and Campania, what has been called Etruria.

The completion of several archaeological excavations in recent years on sites found intact and the restoration of capital works that had been disfigured by interventions in the 19th century, have provided a great deal of additional authentic information for a greater understanding of the dark corners of this subject.

Their deep belief in life after death made them develop a complex system of funerary practices, whose aim was mainly to provide comfort to the dead in their sepulchral abode and to please the gods by filling it with objects that were intended to facilitate their afterlife.

[2][15] Other typologies are also important such as the embracing couple and various statuettes, amulets and reliefs showing images of a strong sexual character, used in a wide variety of ritual conjuration practices.

[17] With respect to their stylistic canons, according to Cunningham and Reich, the Etruscans were not like the Greeks, concerned with deep reflections on the associations between art and ethics or the understanding of how the body functions in an artistic representation and their attention was directed more to the immediate effects of the figures.

[20] Vulci was probably the first center to have a typically Etruscan artistic tradition, manifested in forms of vessels and cauldrons with small groups of figurines of men and animals on their lids.

[2] They are of small dimensions and are mostly utilitarian bronze objects, such as harnesses for horses, helmets, arrowheads and spearheads, pitchers, bracelets, necklaces, as well as cauldrons and pans and other utensils of unknown utility, along with ceramic vessels of all kinds: pots, jars and plates.

[26] Burials were often luxurious, including a profusion of both decorative and sacred objects, the warrior princes, invested in buying sumptuary goods in the likeness of oriental pomps and typologies.

[27] Decorative motifs such as palm leaves, lotus and lion became frequent and good examples are the bracelets and pendants with ivory lion figures found at Tivoli, a silver plaque in relief depicting the "Lady of the wild beasts", of uncertain origin, and the large bronze shields used to hang on tombs, especially those of Cerveteri, decorated with reliefs in a style reminiscent of the geometric patterns of the culture of Villanova, but including other oriental elements.

[24][28] By the end of the period, his artistic production had already succeeded in formulating an aesthetic that consciously surpassed the mere imitation of foreign models and his skill with precious metals and bronze, became known beyond his borders.

[4]The importation of the archaic style from Greece was natural, taking into account the continuity of the strong commercial and cultural ties that united both peoples and favoured by the fact that around 548-547 BC the Persians conquered Ionia, causing the flight of many Greeks to Italy.

Again, the assimilation was not literal, using alternative materials for its construction, showing different divisions in the spaces of the building, in its distribution and design of columns and with the use of many decorative details in terracotta polychrome, such as friezes, acroterion, antefixs and plaques with narrative scenes or with various ornamental motifs.

Massimo Pallottino justifies this difference by saying that classical Greek culture was at that time, for various reasons, more centered in Athens and the Peloponnese and had somehow blocked the influence of its radiation to neighboring regions.

Religion and funerary customs are increasingly simple, as tombs decorated with the luxury of previous phases were not made, nor with so many objects or accessories, suggesting that the interests of society were turning more to the present life than to the afterlife, all the more so because pessimistic visions regarding the future of their people were beginning to predominate.

Although the formal repertoire continues to be varied, around the 2nd century BC the models were already established and the demand was such that it led to their mass production, from the same mold—in terracotta—or from the same model—in stone—with a strong decrease in individualized pieces.

The same happened with the pieces of heads and votive statuettes, their quality also tended to decline, possibly caused by the intensive production of second or third generation molds and the renunciation of manual work after modeling.

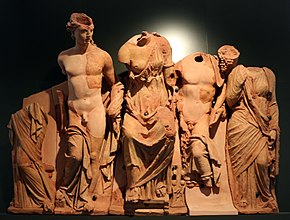

The architectural groups tend to be more populated with figures, arranged in sections that alternated great movement and violence with others of a more peaceful atmosphere and using eclectic resources from various sources, including the archaic.

[37]The vast majority of sculptural remains, both large—architectural statuary and sarcophagi—and smaller pieces, were made in terracotta, whose ease of handling perfectly served the purposes of sculptors and patrons and the great demand for funerary and decorative works.

They were able to add to bronze other metals such as gold, copper or silver inlays and their production had a large market among several of their neighboring peoples, especially the Romans, this being a technique praised by Horace.

[44] In the 17th century the Scottish scholar Sir Thomas Dempster made a significant contribution to knowledge of the Etruscans with the seven-volume work entitled De Etruria Regali, a compilation of ancient sources accompanied by ninety-three engravings showing their monuments.

[45] These pioneering works naturally contained many errors, inaccuracies and false attributions, but they contributed to a first more scientific delimitation of the field of study and also to the gestation of neoclassicism, whose intense interest triggered a collecting fever among European political and intellectual elites.

With Winckelmann, one of the most influential neoclassical theorists, studies reached a higher level, writing extensively on Etruscan art, including sculpture, distinguishing clearly between its style and Greek, he also recognized its internal variations, praised the skill of its artists and considered it "a noble tradition".

[48] Even in the 19th century Etruscan sculpture gained an important forum for discussion when the Istituto di Correspondenza Archaeologica was created in 1829 to promote international cooperation in the study of Italian archaeology, publishing many articles and carrying out excavations in several necropolises.

However, the increasing availability of significant finds caused the destruction of numerous archaeological sites by wreck hunters, disasters denounced by the British consul in Italy, George Dennis in his book The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria of 1848, which immediately became a best seller and whose third edition (1883) remains a good introduction to the subject.

But perhaps more important was the contribution of Alois Riegl, who, although not particularly focused on Etruscan art, definitively established the validity of neoclassical artistic expressions, at a time when the Greek legacy was considered a model.

The cases that had the greatest repercussions were the works created by the family of Pio Riccardi and Alceo Dossena, so well executed that they were acquired by important museums and remained on public display as authentic for several years until the fraud was discovered.

[53] Several institutions in Europe and United States have dedicated in recent decades, significant funds for theoretical research projects, excavations and formation of collections of Etruscan objects and art, contributing to a better understanding of a subject that is largely hidden by unknowns.

Other authors suggest that the Etruscan legacy in central Italy is alive in popular superstitions and religious symbols, in agricultural practices, in certain forms of public celebration, and in the decorative projects of buildings and house interiors, especially in relief carving techniques.