Eukaryote hybrid genome

Although most interspecific hybrids are sterile or less fit than their parents, some may survive and reproduce, enabling the transfer of adaptive variants across the species boundary, and even result in the formation of novel evolutionary lineages.

[1] Traditionally, zoologists have viewed interspecific hybridization as maladaptive behaviour[2] which can result in breaking up co-adapted gene complexes.

[3] In contrast, plant biologists recognized early on that hybridization can sometimes be an important evolutionary force, contributing to increasing biodiversity.

[1] Hybridization is now also known to contribute to the evolutionary potential in several textbook examples of adaptive radiation, including the Geospiza Galapagos finches,[8] African cichlid fishes,[9] Heliconius butterflies[10][11][12] and Hawaiian Madiinae tarweeds and silverswords.

[33] Examples of adaptive traits that have been transferred via introgression include an insecticide resistance gene that was transferred from Anopheles gambiae to A. coluzzii[21] and the red warning wing colouration trait in Heliconius butterflies that is under natural selection from predators which has been introgressed from e.g. H. melpomene to H. timareta[34] and other Heliconius species.

[38] Many empirical case studies start with exploratory detection of putative hybrid taxa or individuals with genomic clustering approaches, such as those used in the software STRUCTURE,[39] ADMIXTURE[40] or fineSTRUCTURE.

An entire suite of methods have been developed to detect such excess allele sharing between hybridizing taxa, including Patterson’s D statistics or ABBA-BABA tests[43][44][45] or f-statistics.

[51][52][53] These methods reconstruct complex phylogenetic models with hybridization that best fit the genetic relationships among the sampled taxa and provide estimates for drift and introgression.

The fit of the demographic models to the data can be assessed with the site frequency spectrum[61][62] or with summary statistics in an Approximate Bayesian Computation framework.

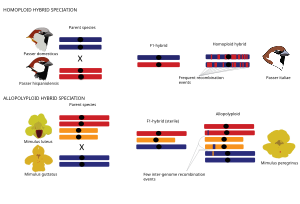

[66][67][71][72][73][74][70] In the case of polyploid hybrid speciation, hybridisation is associated with genome duplication, resulting in an allopolyploid with increased ploidy compared to their parental taxa.

In plants, pollinator mediated isolation resulting from changes in floral characteristics may be an important extrinsic prezygotic ecological barrier.

[82] Lowe & Abbott conclude that selfing, timing of flowering and characters involved in pollinator attraction likely contribute to this external isolation.

[12] Intrinsic differences in habitat use[84] or in phenology[85] may result in some degree of reproductive isolation against parent species if mating is time and habitat-specific.

In Xiphophorus swordtail fish strong ancestry assortative mating maintained a hybrid genetic cluster separate for 25 generations, but disappeared under manipulated conditions.

Introgressive hybridization can transfer important novel variants into genomes of a species that remains distinct from the other taxa in spite of occasional gene flow.

Following initial hybridization, introgression tracts, the genetic blocks inherited from each parent species, are broken down with successive generations and recombination events.

In allopolyploids, recombination can destabilize the karyotype and lead to aberrant meiotic behaviour and reduced fertility, but may also generate novel gene combinations and advantageous phenotypic traits [94] as in homoploid hybrids.

[100] Given time, genetic drift will eventually stochastically fix blocks derived from the two parent species in finite isolated hybrid populations.

This pattern has been detected in monkeyflowers Mimulus,[106] in Mus domesticus house mice,[107] in Heliconius butterflies[105] and in Xiphophorus swordtail fish.

[119][120] Increased transposon activation, as proposed in McClintock's ‘genomic shock’ theory, could result in alterations to gene expression.

[127][128] In a meta analysis, Sankoff and collaborators found evidence consistent with reduction-resistant pairs and a concentration of functional genes on a single chromosome and suggest that the reduction process partly is constrained.

[130] In addition to these changes to genome structure and properties, studies of allopolyploid rice and whitefish suggest that patterns of gene expression may be disrupted in hybrid species.

[136] The absence of heteromorphic sex chromosomes results in slower accumulation of reproductive isolation,[137][138] and may hence enable hybridization between phylogenetically more distant taxa.

A closely related observation is the large X effect stating that there is a disproportionate contribution of the X/Z-chromosome in fitness reduction of heterogametic hybrids.

[22] These patterns likely arise as recessive alleles with deleterious effects in hybrids have a stronger impacts on the heterogametic than the homogametic sex, due to hemizygous expression.

[4] In plants, high rates of selfing in some species may prevent hybridization, and breeding system may also affect the frequency of heterospecific pollen transfer.

[153] Interestingly, Arctic floras harbour an unusually high proportion of allopolyploid plants,[154] suggesting that these hybrid taxa could have an advantage in extreme environments, potentially through reducing the negative effects of inbreeding.

[162] Genes and genomic regions that are adaptive may be readily introgressed between species e.g. in hybrid zones if they are not linked to incompatibility loci.

This often referred to semi-permeable species boundaries,[19][163][164] and examples include e.g. genes involved in olfaction that are introgressed across a Mus musculus and M. domesticus hybrid zone.

[166] This article was adapted from the following source under a CC BY 4.0 license (2019) (reviewer reports): Anna Runemark; Mario Vallejo-Marin; Joana I Meier (27 November 2019).